The below is an excerpt from the 1978 book “Olympic Shooting” written by Col. Jim Crossman and published by the National Rifle Association of America.

BIATHLON

By Col. Jim Crossman

In 1924, a separate program of Winter Olympics was started in Chamonix, France, since it was obvious that the cold-weather sports—skiing, skating, sledding and so on—were not being taken care of under the program then existing. The Winter Games are separate from the regular Olympics and are not merely winter adjuncts to the main games, but completely separate. In fact, not only are the two games held at different times of the year—for obvious reasons—but they are usually held in different countries.

Unless he was very fond of cold weather, the winter games didn’t really have much to offer the shooter. Until 1960, that is, when a new event was added—the Biathlon. This event, combining shooting and skiing, had been very popular in the Scandinavian countries, where it had obvious military value. Over the years, demonstrations of the winter pentathlon (shooting, downhill skiing, 10 kilometer ski run, fencing and horseback riding) and various military patrol events had been conducted, but it was not until 1960 that any shooting event was officially introduced as part of the Winter Games.

The Biathlon is a ski race of about 20 kilometers (about 12½ miles) broken by four shooting events. The skier arrives at a range established in the snow, takes his position on a numbered firing point, and fires five shots at a round, black target placed just on top of the snow with the target number by it. He then fires five shots and hastily takes off again. Targets are not marked until after the shooter has left.

Scoring is literally a hit-or-miss proposition. A miss adds two minutes to the total elapsed skiing time over the course, the winner being chosen on the basis of the least total corrected time. To complicate things a bit, the ranges to the four targets differ, the target sizes differ and two shooting positions are required.

In the 1960 race at Squaw Valley, the first target was 200 meters and was 25 centimeters (a bit less than 10 inches) in diameter, the second was 250 meters with a 30 centimeter (11.8 inches) diameter, the third at 150 meters 20 centimeters (7.9 inches) across and the final target at 100 meters 30 centimeters (11.8 inches) in diameter. Shooting position was optional at the first three ranges, but standing without support was required at the last one.

This tough event is not for the old and feeble. After the competitor has skied a couple of miles at top speed, he finds himself at the first range. He flops down in the snow, gets off his five shots, leaps to his feet as best he can and takes off for a few more miles across country to the next target, which is of a different size and a different range. When the competitor gets to one of the ranges, he is not in very good condition for careful, accurate shooting and is probably tired and winded. As soon as he stops for a moment his glasses steam up. His hits on the targets are not marked, so he has to make his estimate of wind conditions as he goes and must adjust his sights or his point of hold from range to range. Sights are probably snow-encrusted, and if the skier has fallen on the rifle, the sights may have been knocked out of alignment.

Choice of a rifle is wide open. It has to be something that the contestant can shoot well without being too much of a nuisance while being carried those 12½ miles. The American team picked the Winchester Model 70 bolt-action rifle, chambered for the .243 Winchester cartridge. The Swedes used a 6.5 millimeter Mauser, the Russians a 7.62 millimeter Mosin Nagent, France the Remington Model 740 in .30-'06 caliber with the only open sights, and the British stuck to their Short Magazine Lee Enfield No.5 Mark 4 in .303 caliber.

That rifle shooting was a most important part of this event is shown by the results. That the shooting was tough is shown by the fact that only one man made 20 hits on his 20 shots. Klas Lestander, Sweden, had an elapsed time of 1 hour and 33 minutes and 21.6 seconds; with perfect shooting, that was his corrected time. Tryvainen, Finland, finished second with a corrected time of 1:33:57.7, which had been hurt by the addition of four minutes penalty time. The four Soviet entries finished in the next four places, all with good skiing time, but hurt by penalty points in shooting. Of the first 25 in the event, the shortest skiing time was 1:25:58, with the longest 1:40:06, or a difference of about 15 minutes. In the same group, penalty points added for poor shooting varied from zero to 36 minutes. Strangely enough, the competitor with the shortest skiing time, France’s Arben had both the shortest skiing time and the most penalty points, to end in 25th place. Shooting does count in the biathlon!

Once again in 1964, the U.S. ski-shooters—biathlon—did not do too well, the best man finishing in 16th place, well behind Vladimir Melanin of the USSR. One of the major problems with the biathlon in the United States was the relatively low interest in it on the part of civilians. The Army has maintained a biathlon unit for a number of years, recruiting young men with college experience in skiing or regular army enlisted men who have an interest but less experience in skiing. Most of the men with college experience are available for only two or three years, which is not long enough to make them top-notch biathlon competitors and get them through a winter games.

The Biathlon Committee Chairman noted in his 1965 report that another problem for the civilian is the high cost of ammunition, “which runs over $200 per competitor.” This obviously includes a considerable amount of shooting, since at the then price of about 20¢ per shot, this would amount to 1,000 rounds. There is no doubt this is a hardship, but think about the competitive shooter who fires many thousands of shots in a year.

While there are good and sufficient reasons for our poor showing, it is obvious that the biathlon is not our strongest sport!

The ski-shooters of the United States still had not solved all their problems by the 1972 Winter Games, held in Sapporo, Japan. Magnar Solberg, Norway, took the gold medal, as he did in 1968. Although only fourth in the skiing portion, he collected only one minute shooting penalty for overall first. That the United States had some real problems is shown by our placing in World Championship and Olympic competition in the years since 1960. Our best individual position has been eighth, but for the most part we were farther down the list, 14th in 1972 for example.

For a few years, the Army had a Biathlon training center at Fort Richardson, Alaska. But that has been closed and the current U.S. effort is largely based on the work of the U.S. Modern Pentathlon and Biathlon Association. They have an active group in New England who get together on occasion for training, and who put out a newsletter to all biathlon enthusiasts across the country as well as a center at Camp Winooski, Vermont.

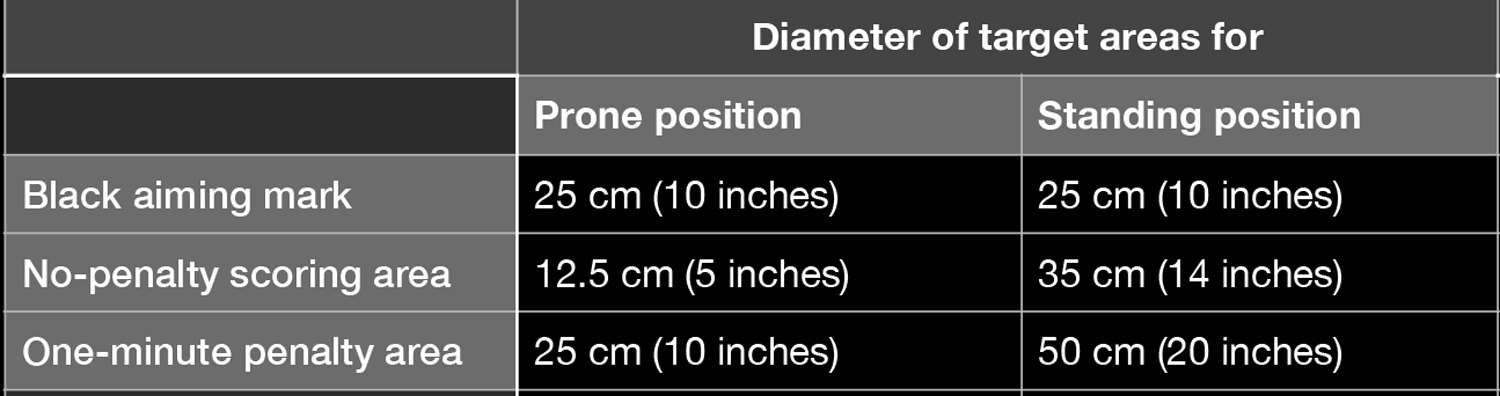

By 1968 the rules for the event had changed somewhat from the original. While the shooter still fired five shots at each of four halts, the target distance remained the same for all the shooting: 150 meters (165 yards). This simplified range construction and permitted the use of a five-loop skiing course, with the start, the finish and the rifle range all close together in the same area. This made it much better for spectators—and TV. Two firing positions were used, prone for the first and third stops and standing for the second and final shoots. Two target sizes were used, one for the prone position and one for the standing. Instead of being a hit-or-miss proposition as it was originally, a new scoring ring had been introduced, which gave only a one-minute penalty. As before a complete miss added a two-minute penalty to the actual skiing time. The new target sizes were:

The new target is somewhat more discriminating and should rank the shooters more according to their ability. In the past, a close miss got the same two-point penalty as a wide miss, but on the new target the “close miss” probably would hit the one-minute penalty area where the wide miss would still be a wide miss. Reduction in the number of distances reduced the problem of sight adjustment or change of sighting point, as well as the problem of correction for wind. The change of one of the optional positions to standing made it tougher on the shooter. Remember he has to ski at least 5 km (3.1 miles) before the first target, with at least 3 km skiing between targets. He is huffing and puffing rather mightily by the time he gets around to each of the shooting events—just when he wants to be the most calm and steady. With the heavy penalties for poor shooting, it might pay the skier to take a little extra time to prepare for the shooting, or for the actual shooting. As we saw earlier, in one event, the man with the fastest skiing time was in 25th place because he had the most shooting penalty. Each man has to work out for himself the right allotment of time for skiing and for shooting in order to end up with the smallest total. The relative proportions might well be different with different men.

By 1968 a new biathlon event had been added, the Relay. Whoever worked up the rules for this used some imagination and worked up a game with much spectator appeal. In the individual race, you cannot tell who has won until the judges finish their computing. But in the relay, it is easy to tell who is leading.

This match includes four-man teams. Each man skis 2.5 kilometers (1.5 miles), stops and shoots at targets, skis another 2.5 kilometers, shoots again, then a final 2.5 kilometers before he tags the next man on his team, who goes through the same procedure. So far, this sounds much like the individual match, but there are a couple of interesting differences.

At one stop, the competitor shoots prone, while the other stop calls for standing. But the interesting thing is that he shoots at a breakable target 150 meters away, and he is allowed eight shots to break all five targets. Instead of adding a time penalty and making the race a bookkeeper’s delight, the rules make the competitor ski an extra distance for every target he leaves unbroken. There is a 200-meter penalty loop in the vicinity of the range, and the lousy shooter becomes intimately familiar with every detail of this loop!

The breakable target is 12.5 centimeters (4.9 inches) in diameter for the prone position and 30 centimeters (11.8 inches) for the standing position. With the breakable targets, it is easy to see how the shooting is going, and with the penalty loop, it is easy to see how the whole match is going.

In 1968 the U.S. relay team took eighth place among 13 teams, while in 1972 they moved up to sixth out of 10 teams. It is obvious that the United States badly needs more endeavor in the biathlon field.

In 1976 we maintained our unblemished record of not doing too well in the winter games event of Biathlon, but it must be admitted that there were some evil forces working against the biathletes. Of the four team members, one never got started in the individual race, as he had been knocked out by the influenza. And another member was disqualified after his rifle broke, under unusual circumstances. The two remaining members did their best, but were only able to finish in 37th and 45th places, out of a total of 51 competitors.

The winner, Kruglov, USSR, turned in a time of 1:14, while the best U.S. competitor, Lyle Nelson, used 1:25, 11 minutes behind. Kruglov missed two targets, as did second place Ikola, of Finland. In third was Elizarov, USSR, with a time of 1:16, and three missed. If he had missed only two targets, the two-minute gain would have put him in first. And in fifth place was Kruglov’s teammate Tichanov, with a time of 1:17—and seven misses! He could have missed five targets and won. So it is obvious that while shooting may not win the Biathlon event for you, it can certainly lose it for you.

In the relay event, you will recall, each member of the four-man team races 7.5 km, with relaxing little halts at the 2.5 and 5 km points. The halt at the 2.5 km mark is so relaxing that competitors all lie down-and then try to hit breakable targets at 150 meters. The next halt, at 5 km, requires that they shoot standing. Misses send the poor shots out to visit the hated penalty course. The USSR team beat out their long standing rivals, Finland and East Germany, by going clean in the shooting phase of the relay. The U.S. team was not so lucky, and finished rather a dismal 11th out of 15 entries.

The Biathletes have had a tough time attracting enough eager young folks to their games. It is pretty well limited to the northern part of the country. When the Army shut down the Biathlon training center in Alaska, this was a real blow. But the biathlon enthusiasts have been working hard at the game, with the main activity centered up in the New England and the Rocky Mountains. Many of the top contenders have spent considerable time with the Army Marksmanship Training Unit, at Fort Benning, Georgia, working on their shooting. But Fort Benning is not a very good place to do much skiing! The development of USOC training centers should be a considerable boost to the Biathlon, aided by some USOC money for a development program.

Since the book “Olympic Shooting” was published in 1976, U.S. efforts in Olympic Biathlon have improved. At the Beijing 2022 Winter Games, U.S. biathlete Deedra Irwin secured the best non-relay Olympic biathlon event finish in history for the United States—Ed.