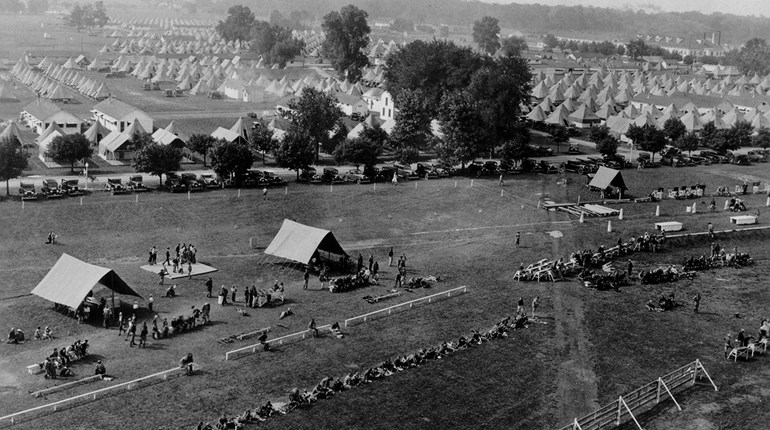

Precision Rifle Series .22 (PRS22) is a relatively new competitive event, but it’s becoming popular. Like centerfire PRS competitions, it involves timed courses of fire with multiple targets of differing sizes at various distances. There is no mandated course of fire, so clubs are free to set up their courses on whatever space they have available. A typical match will have targets scattered at odd distances from 25 to 250 yards. At those clubs that have the room, it’s not uncommon to see targets between 300 and 400 yards thrown in. They may be as small as 1/4-inch plates at 25 and 50 yards, with 4x6-inch plates at the mid-ranges, growing to 18 inches or more at the longer distances.

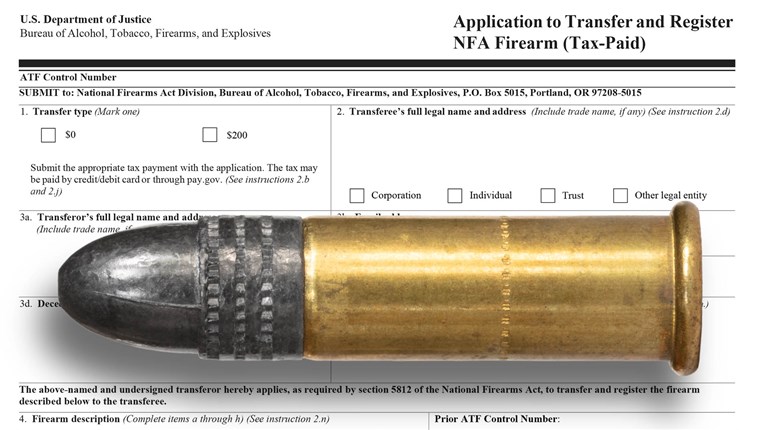

That is asking a lot from a .22 Long Rifle round. Most experienced PRS22 shooters use standard velocity loads because they start subsonic and avoid the accuracy-ruining turbulence caused by a high speed bullet losing velocity and hitting the transonic point (transitioning from supersonic to subsonic velocity), which can destabilize the bullet in flight.

Those distances also ask a lot from a scope.

The trajectory of a .22 Long Rifle round bears a strong resemblance to someone falling off the top story of the Empire State Building. There are various ballistic tables for the round, and all I’ve seen are contradictory. I have viewed ballistic charts based on 50- or 100-yard zeros that show anywhere from 51.5- to 130-inch drops at 300 yards. I have seen nothing mentioning drop between 300 and 400 yards, but I bet it’s a bunch. Few, if any, scopes have that much adjustment. Experienced PRS22 shooters favor first-focal plane scopes in the 5-25X range with a mildot “tree” reticle. They can use the different dots above and below the crosshairs for different ranges. But they still may not have enough adjustment to deal with the longer ranges, since they’ll likely use as much as half of their adjustment range to get a base zero.

Ruger’s newest 10/22 offering provides a solution. It features a 30-MOA Picatinny rail that provides some help with longer ranges.

THE GUN

Ruger’s 10/22 Model 31227 (MSRP: $1,129) sports a free-floated 16.1-inch barrel. Made of cold hammer forged stainless steel, the tensioned barrel is wrapped with a carbonfiber sleeve. The barrel has the standard 1:16-inch right-hand twist and is threaded for muzzle accessories. The test gun arrived with a cylindrical muzzle brake installed. The operating action looks like the standard 10/22, but two subtle changes were made. The magazine release has been moved to the front of the trigger guard with slight protrusions on either side that now allow the magazine release to be conveniently operated with the trigger finger. Like other Ruger 10/22s, the bolt does not lock back on an empty magazine. Locking the bolt back requires diddling with the little lock back lever just forward of the trigger guard. Unlike the rest, releasing the bolt doesn’t require re-diddling with the lever. Just pull the bolt back and let it fly. The two new features are a shooter-friendly upgrade.

Ruger’s BX Trigger is standard. I have it on my two 10/22 Steel Challenge guns and love it. On my digital gauge, this BX trigger measured 2.6 pounds with a crisp break, minimal pre-travel and a fast reset.

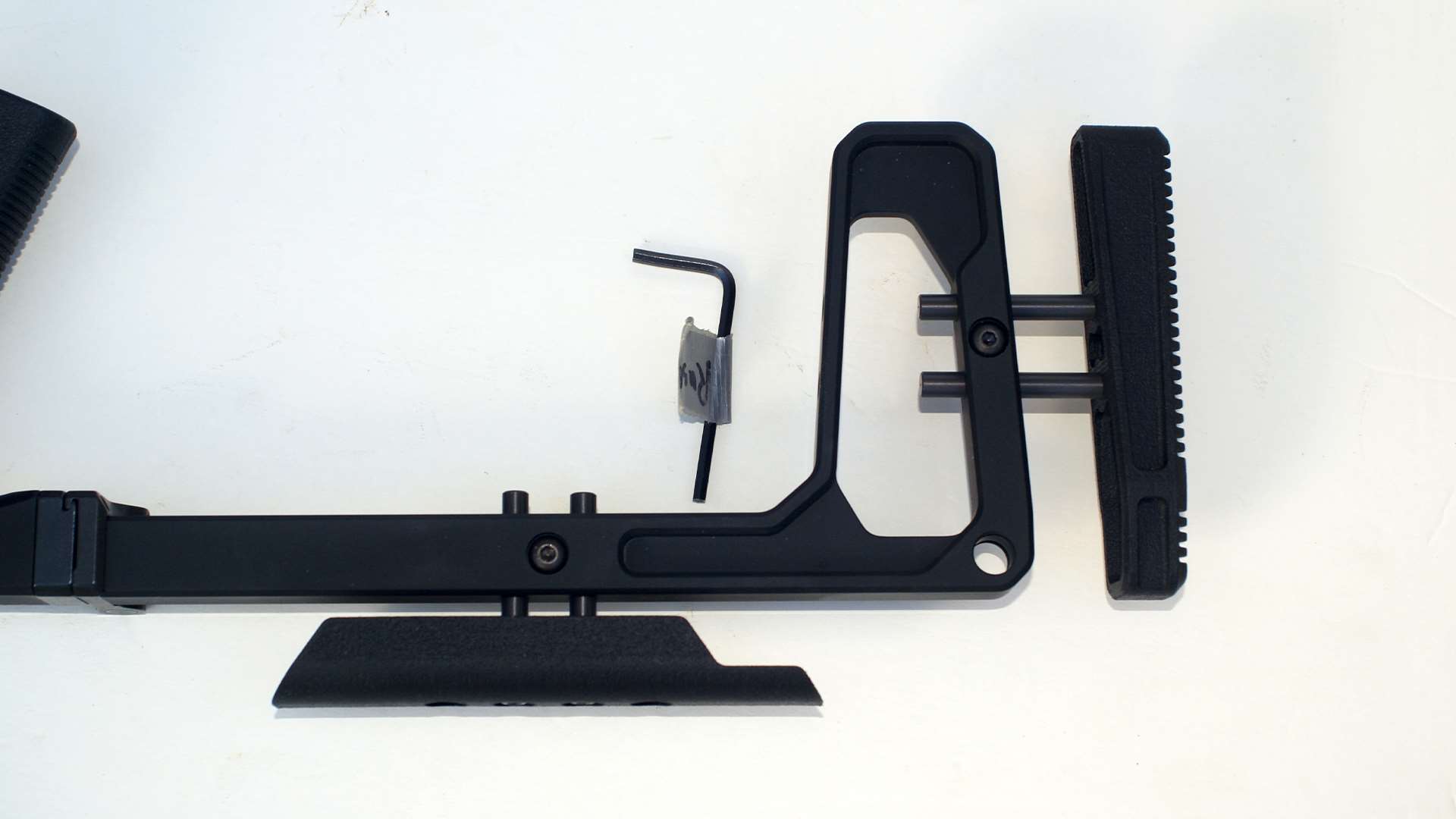

All of this is installed into a Grey Birch Chassis featuring an AR-style pistol grip, modular 10-inch fore-end with M-LOK and Arca-Swiss compatibility. The stock is adjustable for length of pull from 13 to 14½ inches, with an adjustable comb. The stock also folds for easy transport. Dual bedding incorporates a second bedding lug and a top barrel locator allows for a free-floating barrel. Empty weight is 4.2 pounds.

There are no iron sights, nor is there a provision to install any. A 30-MOA Picatinny rail is integral with the receiver. It cants the line of sight down below the line of bore.

The Ruger Model 31227 ships in a hard plastic case with one magazine.

ON THE RANGE

My first step with any test gun is a quick barrel check and lube. While doing that I noticed a very slight “wiggle” in the barrel. I checked the three tension screws located on the underside of the stock just forward of the magazine well and found the rear one slightly loose. I found the appropriate Allen wrench and tightened it down. This is something shooters should watch, because my previous experience has shown that loose tension screws can cause extreme vertical stringing.

With that done it was range time. I was curious as to how the 30-MOA ramp would affect closer range shooting. One MOA equals 1.047-inch at 100 yards, so a 30-MOA rail would theoretically put the line of bore 31.41 inches above the line of sight at 100 yards. I mounted a Holosun 507 reflex sight that had performed perfectly on my 10/22 Steel Challenge rifles and headed to my backyard range. Using the CCI Mini Mag, I found that with the elevation dial bottomed out I was still six inches above the aiming point. It doesn’t look like this gun is suitable for closer competitions, except for Know Your Limits matches with the proper scope.

I then dug out my Baush & Lomb 6-24X Elite 4000 scope that has served me well in past years on western prairie dog shoots. It has a custom reticle, with 1/16-MOA crosshairs and three 1/8-MOA dots above, below and to the sides from the center 1/8-MOA dot. It’s not a first-focal plane scope and the dots change their spacing with magnification changes. I tried zeroing it at 25 yards but with the elevation bottomed out, I was still six inches high. Juggling the magnification, I found an upper dot that zeroed slightly high at 25 yards.

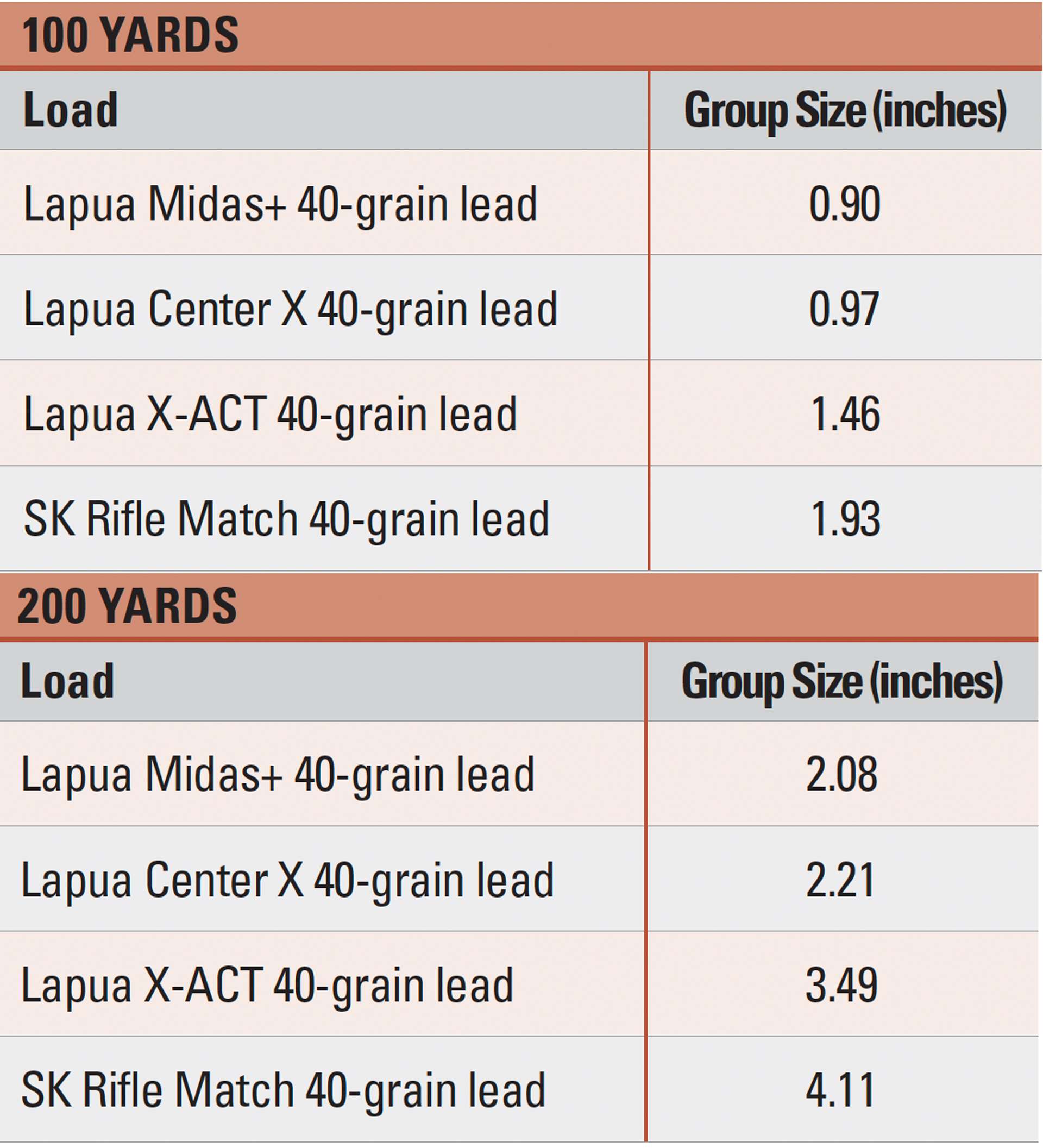

The next stop was my club’s 100-yard range. It was a hot day, but the wind was a gentle breeze blowing directly at my back. I used a large white sheet of paper to which I had taped Factory Class .22 LR sighting squares. They measure 2½ inches and provide a precise aiming point for the 1/8-MOA dots. I fired one round wide, to avoid a cold bore shot, and then fired a five-round group with Center X at a dot at the top of the target. I used the same upper dot/magnification setting as made the 25-yard zero. The group was about 10 inches low but the tight cluster of holes was easy to see. I did the same “juggle the magnification, find the dot” as I had during the initial zero, added a bit of right windage to keep the group out of the aiming point and grouped the remaining loads. Next, I changed the target and did it again. The accuracy table shows the results, but I wasn’t overly surprised. On my 25-yard bench, the three-shoot groups I used to zero were invariably touching, and sometimes just one ragged hole.

After packing those targets away for later measurement, I headed to the 200-yard range. I headed to the 200-yard range. Fortunately, there was an electric golf cart available, so I didn’t wear out my shoes changing targets. After viewing the 100-yard targets, I dropped the CCI load from the 200-yard tests.

At 200 yards, I used two Birchwood Casey Dirty Bird targets, one below the other (making the groups easier to see) with the taped squares. The procedure was the same—shoot a group and match the dots to find the aiming point. By this time, the drop was enough to use the center crosshairs with only minor upward scope adjustment.

Targets beyond 200 yards were not available. But if they were, I still had virtually all of the scope’s up elevation remaining, along with the three bottom dots. That 30-MOA rail does take a big bite out of bullet drop. And judging by the group sizes this new Ruger has the accuracy capability to make use of it.

ACCURACY TABLE

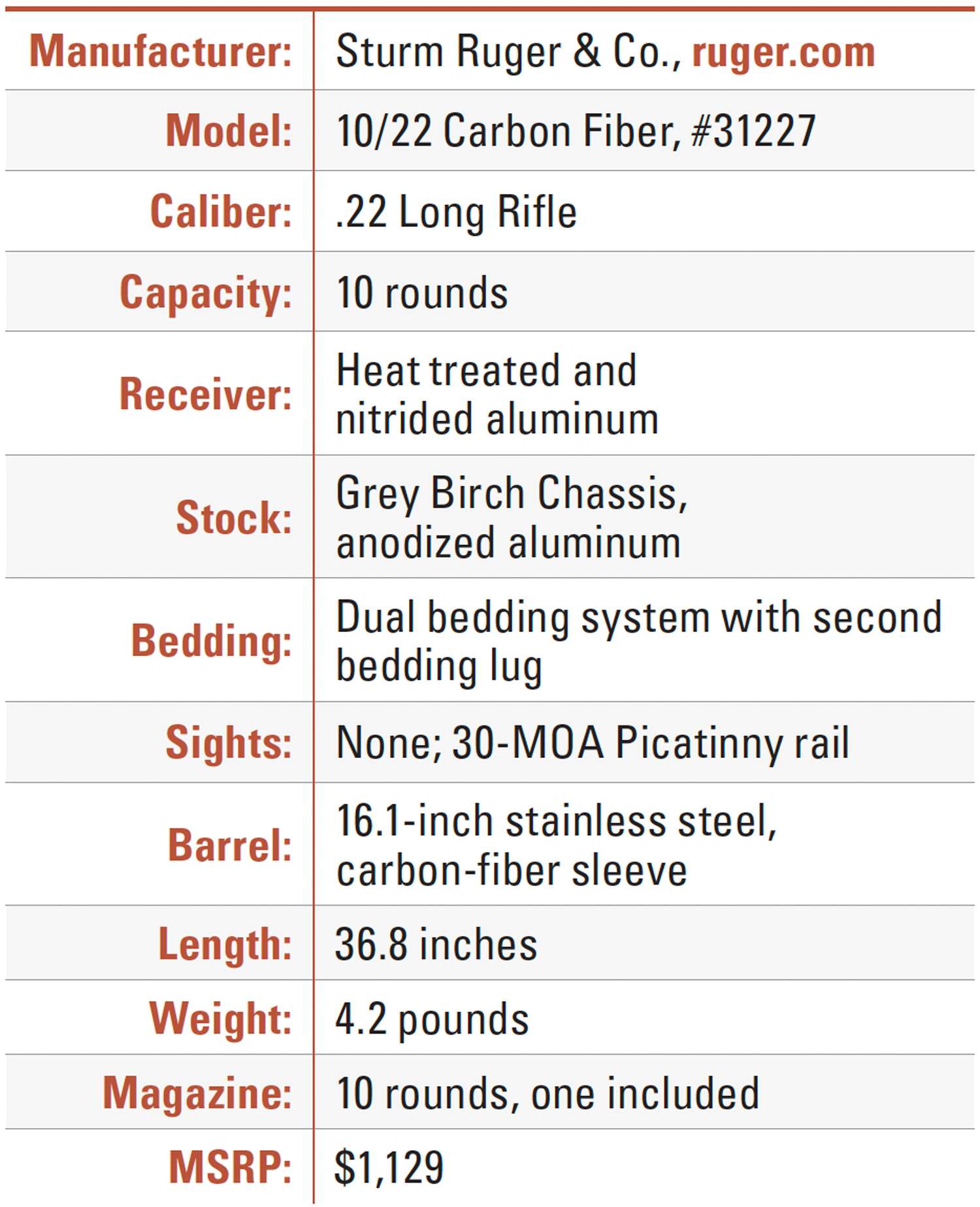

SPECIFICATIONS