Wax bullet cartridges are fun to shoot and easy to make, the only reloading tools required being those for seating and removing primers from a cartridge case. Beyond the simple pleasure of shooting in your parlor, they can also serve as educational or training aids. Yet, few shooters seem to have caught on to this DIY amusement.

Trending now?

Wax bullets, popular today for Cowboy Fast Draw competition, are not new. Nor are today’s wax bullets composed of real beeswax wax, instead typically being a melding of paraffin wax and a plastic, such as polyethylene. Actually, there may never have been a beeswax bullet of any note, but reloading with bullets made of paraffin wax was once fairly popular, when 1950s TV westerns prompted shooters to invent fast draw competitions.

Wax bullet reloading appears in the 1962 Handloader’s Digest in the very first issue, with a full-page listing tools, “special wax compounds” and cartridge cases with pre-drilled flash holes offered by CCI, Lyman and others taking advantage of the fast draw vogue. By the Fourth Edition, the emphasis was on plastic bullets; the Eighth Edition has a single listing for a Forster wax bullet kit. By the 13th Handloader’s Digest, wax bullet reloading had gone the way of the yo-yo and poodle skirts. Such is the nature of trends.

Non-lethal dueling

The earliest references I could find to serious (if I may use the term) employment of wax bullets is to a Parisian “school of dueling” in the early 1900s, and to a dueling competition demonstrated at the 1908 Summer Olympics. In both venues, the duelists fired a round wax ball from single-shot muzzleloading percussion pistols. Safety equipment included what appears to be a fencing mask mounted with a glass plate for clear vision, heavy canvas clothing and a finger-protecting guard mounted on the front of the pistol’s trigger guard. The competition never caught on, but if I you’d like to revive the concept for another go in the 21st century, perhaps including rapiers will add interest—if the duelists both miss with their wax bullets, they can revert to the sword.

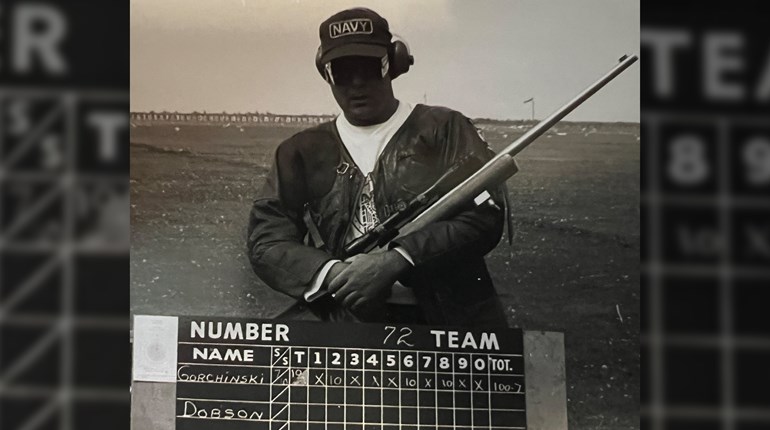

My own foray into wax bullets only goes back to the 1980s, when I shot my milsurp .380/200 No.2 Mark I Webley revolver in my garage. The .380/200 is simply the .38 S&W cartridge with a 200-grain bullet in British uniform, and the cartridge case is slightly larger in diameter and shorter than the .38 Special. While one may shorten .38 Special cases to fit in a .38 S&W chamber, I found their smaller diameter caused cases to split when they expanded upon firing a load of powder and bullet. However, after trimming to .38 S&W length, the .38 Special case performs flawlessly as a wax bullet cartridge in the Webley.

After making up my first batch of “loads” I fastened a paper target to the side of a cardboard box and fired from about 15 feet away. The wax bullets penetrated the side of the box and came to rest inside. When I fired them all I recycled them to melt for another reloading. Curious about the wax bullets’ flight at longer distance, I fired them at a target attached to the back yard wooden fence about 50 feet away. I could clearly see the bullets curve off to the right, induced by the Webley’s right-hand twist.

Cheap and easy

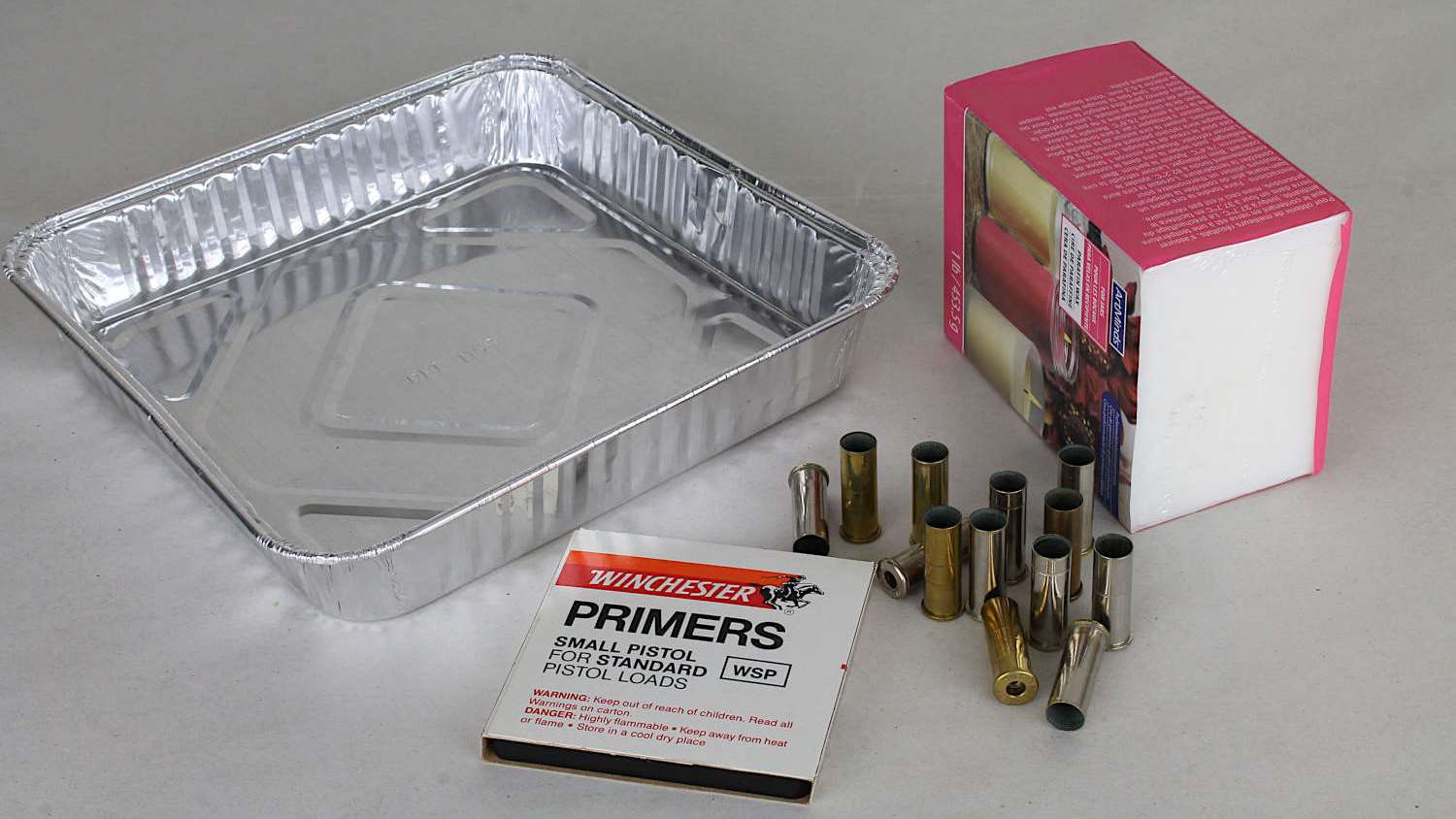

Beyond the aforementioned priming and depcapping tools, the only other reloading accessory you’ll need for making and loading wax bullets is an old pie pan or disposable aluminum pan. Whatever you use for containing the melted wax, note that the diameter of the bottom of the pan and the amount of wax you melt will determine the length of the wax bullet. Happily, wax bullet length is not critical for the cartridge to work, and you may discover some educational entertainment in trying bullets of differing lengths.

Small blocks of paraffin wax are available from grocery, hardware and art stores for about $5 each. One block will keep you in wax bullets, if you recycle and reload them, pretty much until the 2108 Summer Olympics. Paraffin melts at around 180°F; it’s a simple matter to melt the block in the pan in your oven, but keep in mind that paraffin is flammable, so be careful to control melting to avoid overheating or spillage. Before placing in the oven, place your pan “melting pot” on a cookie sheet to catch any accidental spill, and don’t try to hurry up the melting by turning up the heat.

After melting, when the cooling wax has reached a semi-hard state, push your empty cartridge case (here, I demonstrate with .38 Specials) into the wax until it reaches the bottom of the pan. Withdraw the case and the wax bullet will come with it, seated in place flush with the case mouth, like a full wadcutter bullet. Now seat a primer, and you are done.

The primer alone drives the wax bullet; burning at around 3,200°F and more, a charge of smokeless powder would, as you can imagine, pretty much vaporize the wax bullet. Seat primers after seating bullets. If you seat a primer first, attempting to seat the wax bullet compresses the air in the case, and the compressed air pushes the bullet out. Without a primer installed, the air can escape through the case’s primer flash hole, preventing protruding wax bullets.

Enlarge flash holes

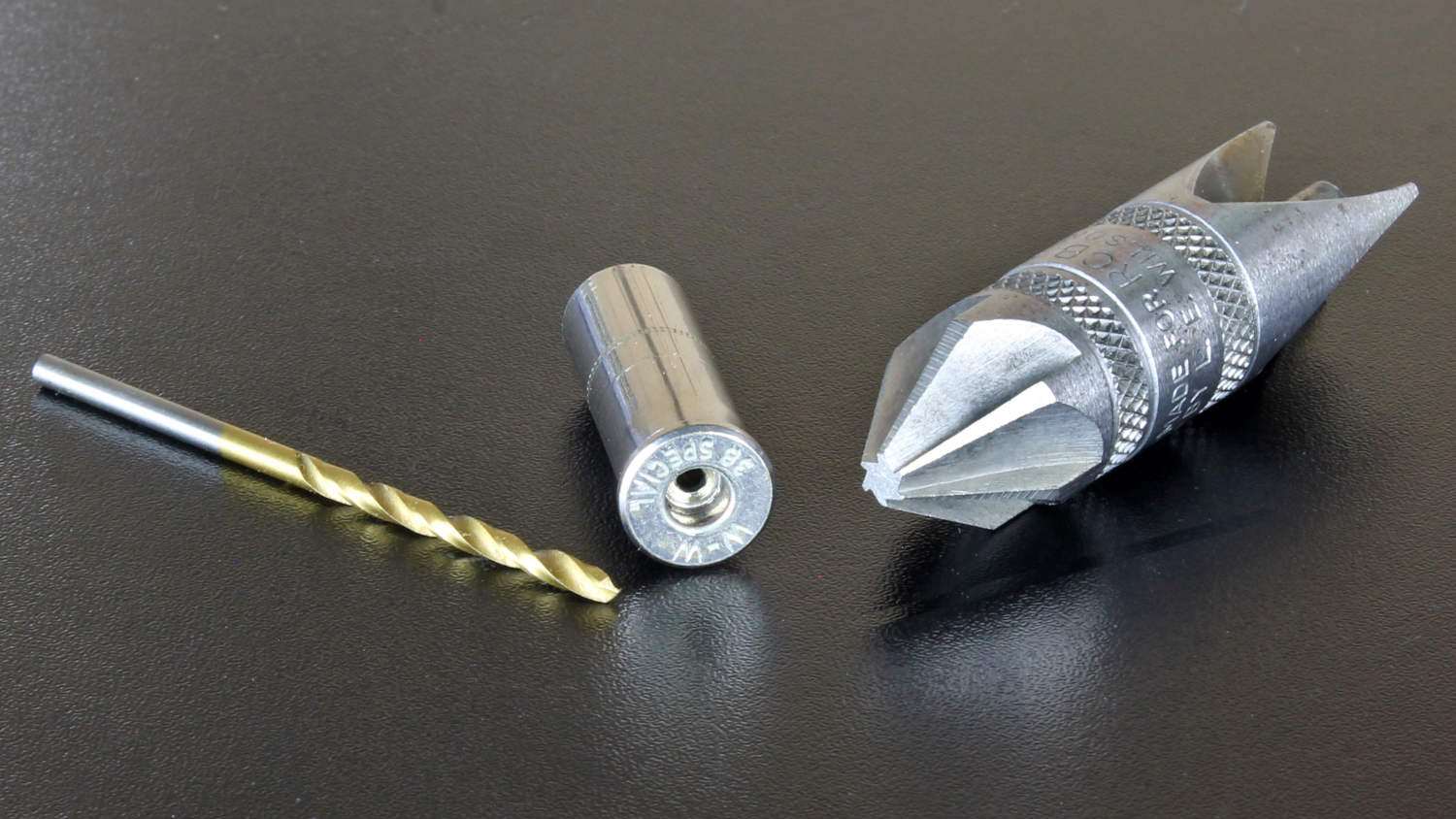

Here we can insert a couple of options. The first is to bevel the case mouth, if you feel it will cut a cleaner wax bullet as the semi-hard wax cools and hardens even more. The second option is less subjective and based upon the experiences of wax bullet shooters since at least the 1950s. If upon firing you notice the primers tend to back out of their pockets—which could interfere with revolver cylinder rotation—the cure is to enlarge the primer flash hole with a 3/32 drill. If you do this, be sure to segregate these cases and earmark them only for wax bullet reloading.

By now, you will realize that primer driven wax bullet cartridges are unlikely to cycle semi-automatic actions, hence revolvers being their natural habitat. But they’ll work in other manually operated repeaters and, of course, in single-shot actions, too.

Educational, entertaining

The wax bullet trend may or may not be back on the upswing. Like most things here in the gee-whiz future, technology has evolved wax bullets from paraffin to plastics or composites, and specialty shops once again sell lines of tools, special lubricants, cleaners and other complications that all such advancements over simplicity seem to bring with them. Certainly, these newer products bring benefits to the competition shooter and to those who utilize other such non-lethal ammunition for training purposes. But for the pursuit of curiosity and simple amusement, they are no more necessary than the specialty tools offered in the old catalogs.

Outside of those fast draw pursuits, wax bullets have an obvious application in introducing a new shooter to our sport. With only modest noise and virtually no recoil, it’s a less intimidating way to start off the interested but timid neophyte. They might also have an application in introducing a youngster to the art and science of handloading. Especially, the concept serves as an excellent demonstration of the power of primers. As well, because the wax bullet in-flight is clearly visible to the shooter when fired over that previously mentioned 50 feet, it can serve to illustrate the concept of rifling-induced drift.

Non-lethal dueling? Maybe not. But there are plenty of other reasons to dabble in wax bullets, not the least of which is entertainment.

Read more articles from Field Editor Art Merrill: