The day begins with a hush that feels like ceremony. The Lake Erie breeze lifts the wind flags in a long breath. Out past the firing line the pits hum with activity, scoreboards clack and the morning light sharpens edges the way a good sight picture does. What follows across this decade will be measured in sight alignment and trigger press, in wind calls and nerves held steady. Shooters at the 1920s National Matches in all disciplines made the 10-ring a shared language and the range a classroom with a view.

1920 — Records Fall and the Modern Matches Take Shape

Camp Perry returned to center stage in 1920 after winning the National Board’s vote over Jacksonville. Ohio’s invitation carried both history and promise, and the Board again turned to Lt. Col. Morton Mumma, whose steady leadership shaped the character of the National Matches that year. His reforms simplified civilian travel reimbursement, expanded national team staffing and required all newcomers to pass through the Small Arms Firing School, a change that strengthened the teaching culture spreading through clubs and Guard units nationwide.

Behind the scenes, Capts. Julian Hatcher and Glen Wilhelm elevated standards by selecting arms and ammunition with unprecedented precision. Wilhelm even entered events himself to verify the effects of their choices. The result was unmistakable. Long-standing records toppled and scores once considered untouchable suddenly became attainable. In the Wimbledon Match two shooters, Navy Lt. Y. A. Yancy and civilian W. R. Stokes, fired perfect scores and then broke the tie with one more shot each. Yancy’s four beat Stokes’s three, a moment that stunned veteran spectators who had believed perfection in that event still belonged to the realm of theory.

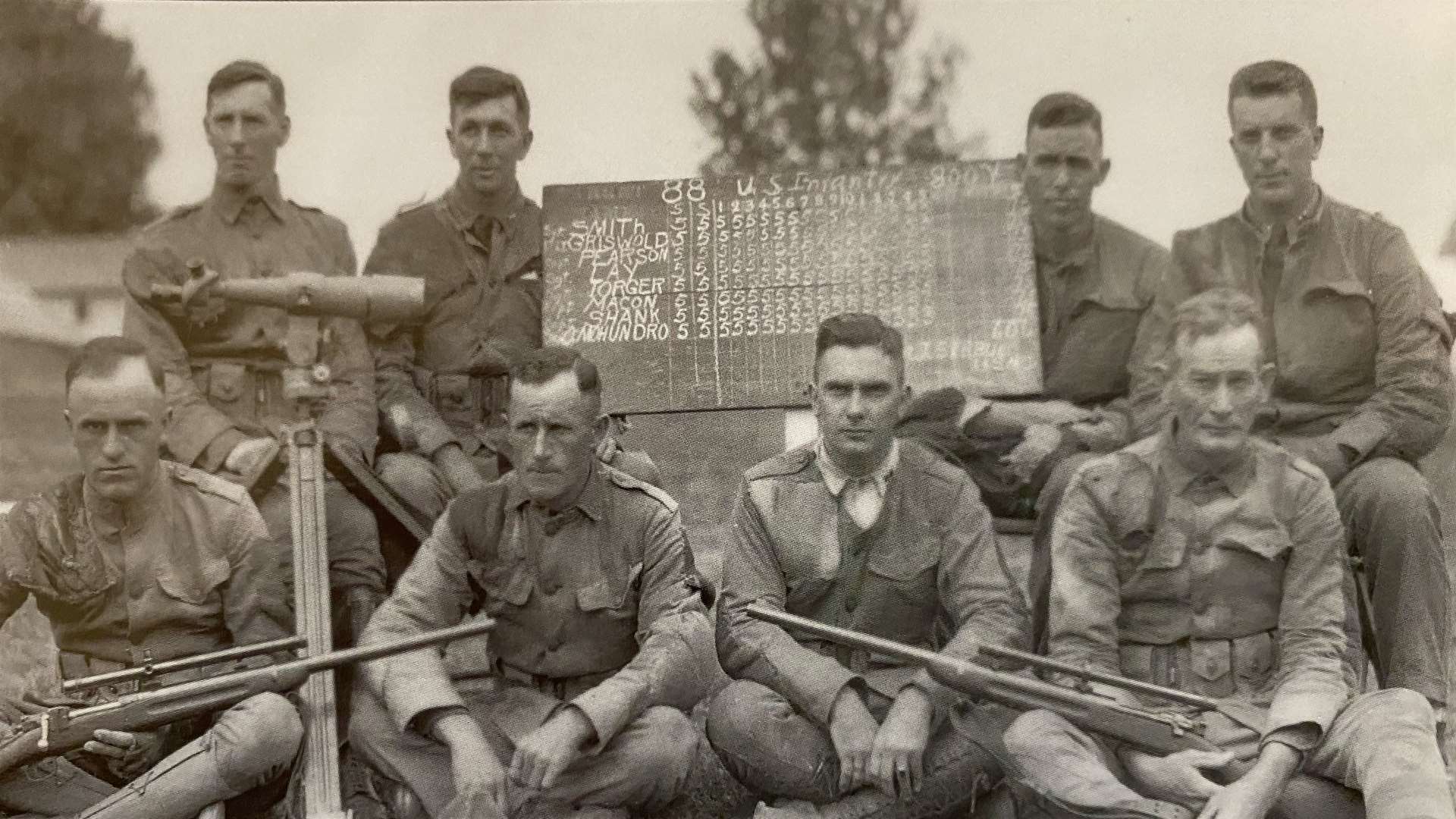

Marine Sgt. T. B. Crawley dominated the long-range program with a perfect Leech Cup score and an extraordinary run of bulls at 600 yards in the Members’ Match. His consistency across the Leech, Members’, Wimbledon, Marine Corps and President’s Matches carried him to the Grand Aggregate title. The Infantry won the National Team Rifle Match among 65 squads, restoring prone fire at 600 yards and Target D to the course. Sgt. H. Whitaker added the National Individual Rifle championship to the Army’s tally.

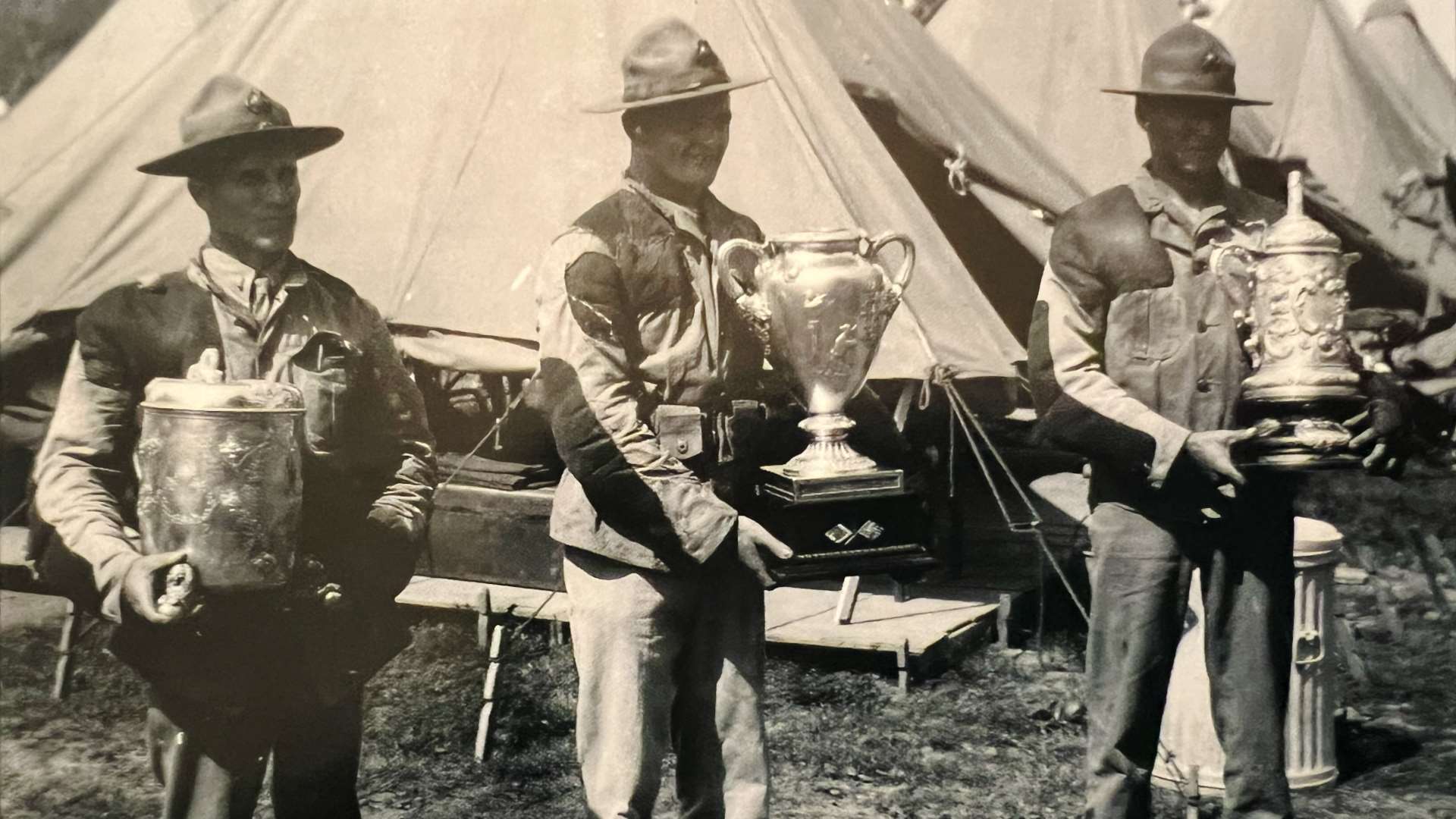

Pistol competition entered a new era with the debut of the National Trophy Pistol Team Match, fired with slow fire at 50 yards and rapid and quick fire at 25. The five-man Marine team claimed the inaugural title and with it the Snyder Trophy, a gleaming gift from the Chinese government to the American Expeditionary Force after the 1919 Inter-Allied Championship. The event sparked debate over the limitation to the Model 1911 .45 automatic, since NRA events still welcomed revolvers and automatics .38 and larger. Arms and the Man urged flexibility, arguing that the National Matches existed to bring all shooters together rather than to sanctify existing experts.

Smallbore provided the year’s longest and most surprising story. More than 200 shooters filled the covered 100-foot firing line at the edge of the 1,000-yard facility. Possible scores appeared at 100 yards for the first time. Marine shooter L. E. Wilson edged Army Capt. W. H. “Cap” Richard in the Grand Aggregate with 690 of 700, though Richard later took the national individual metallic-sight title on a Dewar tiebreaker after both posted 394s. The U.S. Dewar team again defeated the British, maintaining an unbroken chain of victories stretching from the pre-World War I era.

The range that year also embraced the inventive. The Air Service staged an Airplane Match, with a De Havilland from nearby McCook Field taking the title with 295 hits. Commercial Row, now housed in wooden buildings rather than tents, became a technical hub where shooters compared notes and carried new ideas home. By season’s end pistol, smallbore and service rifle felt like a single organism. The term National Matches had come to mean the whole living program.

1921 — Rising Scores and a Wider Door

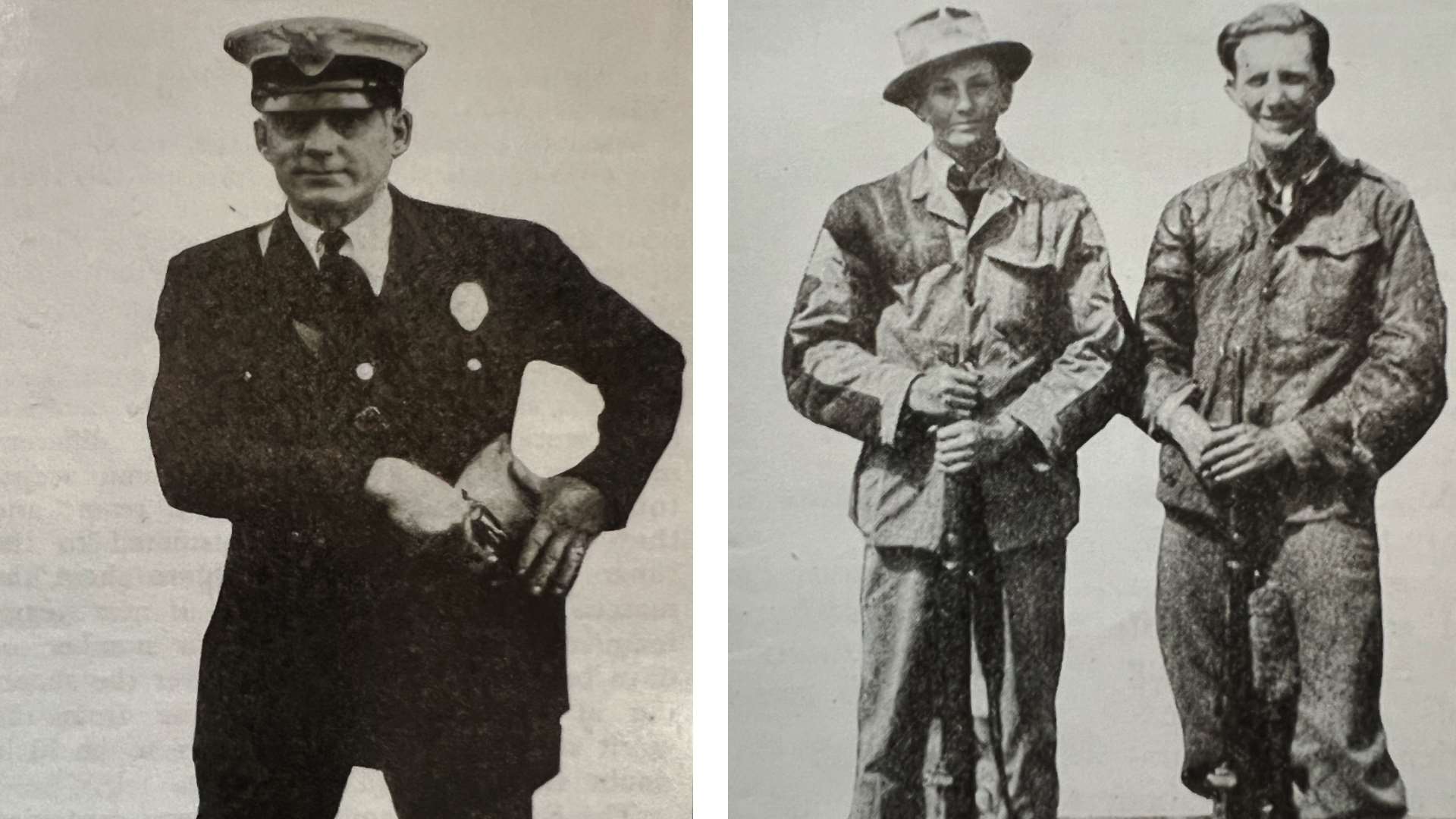

Camp Perry again won on practicality, with much of the infrastructure already in storage on the shore of Lake Erie. Gen. Ammon Critchfield kept the police match alive. Col. Charles Stodter, the new Director of Civilian Marksmanship, pushed for more offhand stages and a moving target competition. Lt. Col. Mumma led a staff that included six past NRA presidents, proof of the NRA-Board alignment that now defined the enterprise.

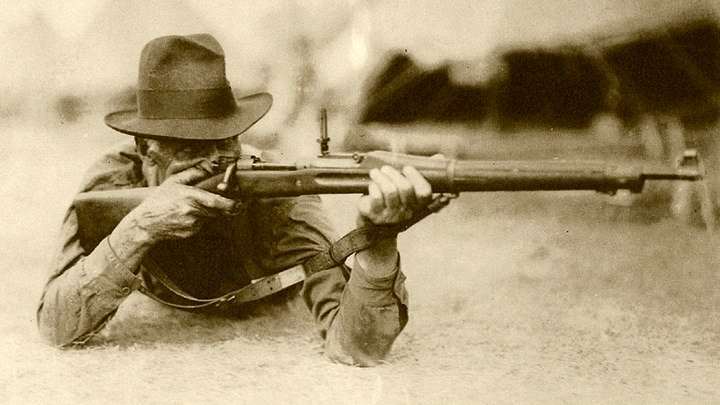

Scores climbed to heights that startled veterans. Telescopic sights, excellent Frankford Arsenal ammunition and new Springfield rifles raised expectations across the board. Sgt. T. B. Crawley ran 176 consecutive bulls at 800 yards in the Winchester Cartridge Company Match. Sgt. J. W. Adkins stacked 80 straight at 900 yards and 71 centers at 1,000, then won the Wimbledon Cup with 75 bulls at 1,000 yards. The runner-up nearly stole the legend. George “Dad” Farr, a 62-year-old civilian firing a service rifle with sights issued that morning, struck 70 straight bulls before darkness forced him to stop. His teammates later bought him the rifle.

The Marines swept the Board’s pistol matches and clawed back from a 22-point deficit to defeat the Infantry in the National Team Rifle Match after a heavy downpour destroyed scorecards and both captains agreed to restart the stage. The year also introduced the National Intercollegiate Rifle Team Match, with the Naval Academy taking the top three positions among 18 teams. Shotgun competition boomed with more than 100,000 targets thrown in 13 days. The All Round Match went to Pennsylvania civilian Charles Hogue, underscoring the program’s broadening appeal.

Smallbore overflowed despite complaints about the distant range. Procedures tightened with clear time limits and crossfire penalties. Juniors like Marjorie Kinder proved the pipeline was real. Milo Snyder of the Indiana National Guard became the first shooter to win both the metallic-sight Dewar National Individual title and the smallbore Grand Aggregate. The U.S. again held the Dewar Trophy, with British officials noting America’s edge in selection matches and active line coaching.

1922 — A Test of Resolve and a Triumph of Craft

In 1922 the National Matches opened under a shadow that had nothing to do with the weather. Congress declined to provide federal travel funds for civilian or National Guard teams, announced in July with barely two months before the start. NRA refused to let the program falter and urged competitors to come despite the cost. Only Illinois and Indiana could send full civilian teams, yet more than 200 non-service competitors still made the trip at their own expense. National Guard entries came from 32 states.

Those who came produced performances worthy of a far more stable year. The Massachusetts National Guard won the Herrick Trophy with a score that surpassed the Palma record. Civilian Loren Felt of Illinois won the Leech Cup with a perfect score under the revised V-count system. Capt. Guy Emerson of Ohio claimed his third Wimbledon Cup with 100-15V. The NRA created a separate recognition for high shooters using as-issued service rifles, inspired by George “Dad” Farr’s remarkable 1921 run. Pvt. Louis Klinger of the Cavalry won that honor with 100-8V.

In the Board matches the Marine team held the rifle title with the Model 1903 Springfield firing 170-grain boat-tailed gilding metal bullets. Sgt. Otto Bentz of the Coast Artillery topped the Individual Rifle Match, still without a 1,000-yard stage. Lt. Eduardo Andino won the Individual Pistol Match as 50-yard competition returned to the course. Lt. Col. Mumma completed his fourth year as Executive Officer, earning a silver pitcher from the NRA. Under his guidance the National Matches ran without a single schedule change or weather delay.

Smallbore survived the funding setback through loyalty and momentum. Felt himself proved the value of the .22 when his Perry re-entry practice sessions preceded his Leech Cup victory with the service rifle. The debut of the Springfield .22, engineered with NRA collaboration, further strengthened the discipline. Capt. J. E. Hauck of the Indiana National Guard won the smallbore national title. The U.S. Dewar team, half of them civilians who paid their own travel, fought through punishing Lake Erie winds to defeat the British by 70 points.

1923 — Expansion, Innovation and the Growing Pains of Success

Federal travel remained unfunded for a second straight year, so the NRA revived reduced rail fares. Lt. Col. Mumma, directing his fifth National Matches, expanded the Small Arms Firing School to train railroad mail clerks after a spate of train robberies. The NRA’s young police training program managed to field eight police teams, the largest showing to date. International scope returned with free rifle and pistol events and the revival of the Palma Match after a decade of silence.

More than 1,100 competitors took part, including more than 100 civilians who paid their own way. A rule prohibiting organizations from fielding secondary teams made the 65 official squads a true cross-section of American marksmanship. The Marines and Infantry split Board honors, with Lt. L. V. Jones winning the individual rifle title in a field of more than 1,000 entries. Firing at 1,000 yards returned to the individual rifle program, and a new rapid-fire Target A was introduced to counter the rising tide of perfect scores.

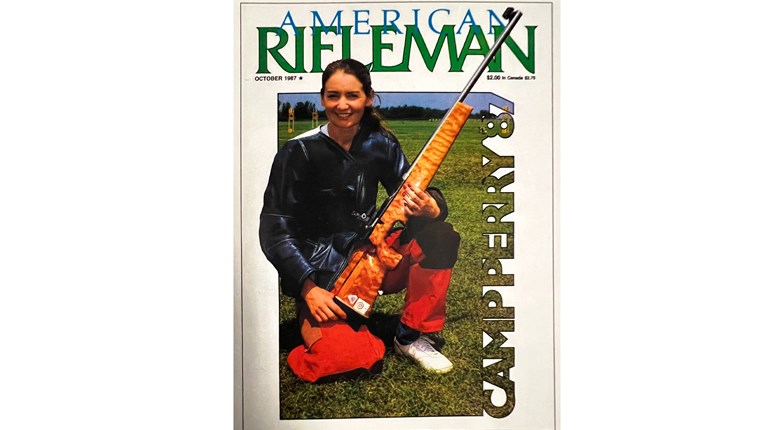

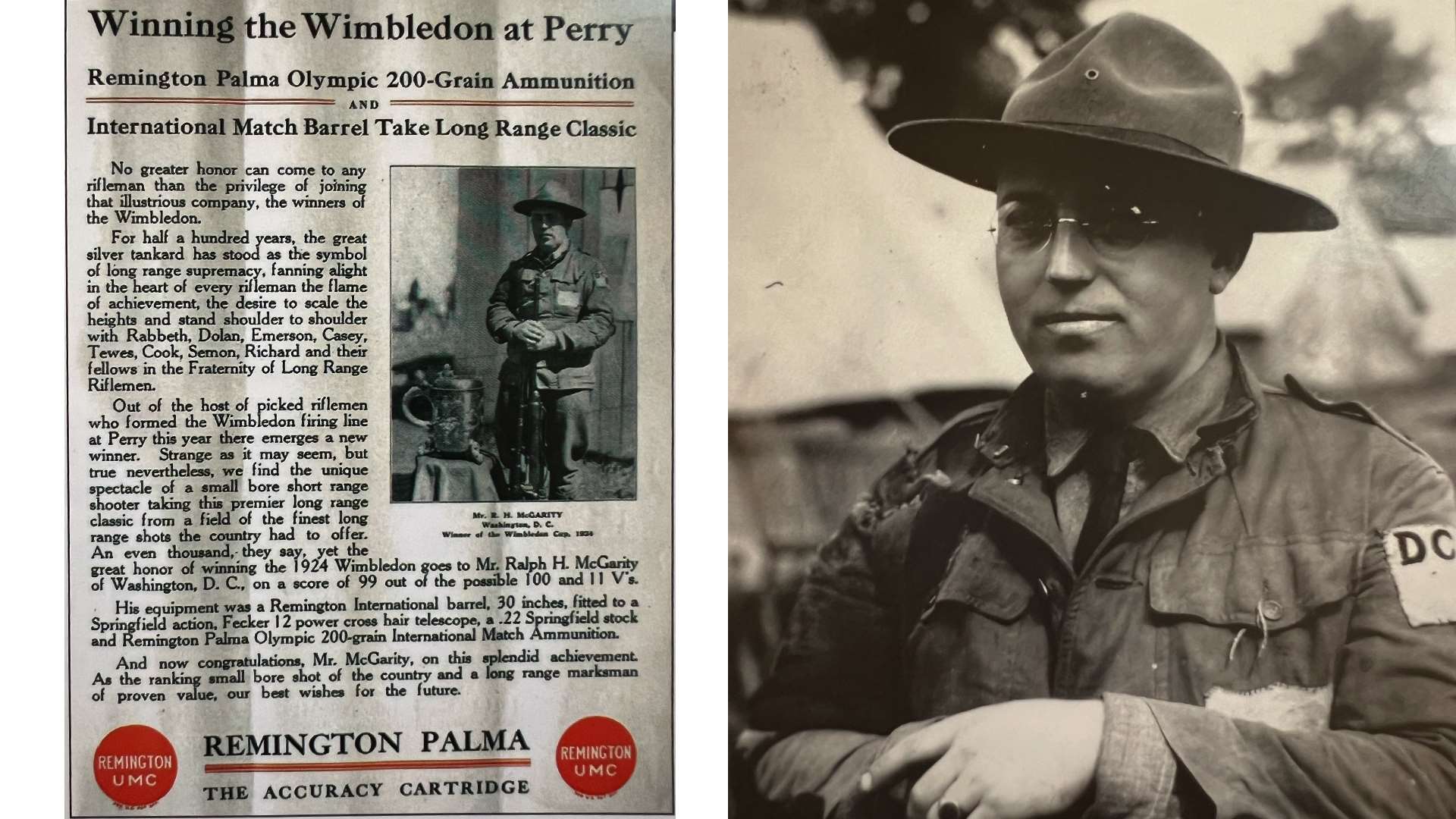

On the NRA side Sgt. E. J. Blade won the Wimbledon Cup, Lt. P. E. Conradt took the President’s Match and Sgt. William Hayes claimed the Leech Cup. But the center of gravity was smallbore. The range moved from the outskirts of camp to a new home between the 200- and 300-yard firing lines, placing the .22 game in the heart of the National Matches. A narrow-gauge track system replaced the old runner-supported frames, creating a safer and more efficient target service. Ralph McGarity of Washington, D.C., won the National Individual Smallbore Championship over a new any-sight course at 50, 100 and 200 yards. The U.S. earned its fifth straight postwar Dewar victory despite heavy winds.

The Winchester Junior Rifle Corps ran a one-week camp for 40 boys and girls, mixing instruction with cheerful novelties like shooting at animal crackers in a “Big Game Shoot.” Junior Russell Wiles, Jr., posted a 394 of 400 on the Dewar team, embodying the push to bring younger shooters into the culture. More competitors, more juniors, more nations and more technical innovation created a sense that the National Matches was beginning to stretch at the seams.

1924 — The Art of Straight Shooting

After two years of tight budgets, the War Department restored federal funding for civilian and National Guard travel. Congress tied its support to a clear purpose: at least half of all service-class shooters had to be new to the National Match Rifle Team. The message was unmistakable. The government wanted the National Matches to train new marksmen, not reward the same elite year after year.

A smallpox outbreak forced competitors to show proof of vaccination or receive one on site, with more than 400 lining up during the first week. New events followed. The Chemical Warfare Match debuted at 200 yards, shot while wearing gas masks, with Navy Lt. Van Rathbun winning. Free pistol joined the 50-yard slow-fire program. A dedicated smallbore committee formed and called for a permanent range and squadded relays.

Team rifle drama peaked when the Coast Artillery edged the Marines in the Herrick Matchon the final shot by four points, and the Oregon National Guard dethroned the Infantry in the Infantry Match. Ralph McGarity won the Wimbledon Cup with a borrowed scoped rifle after posting 125 straight bulls at 200 yards in a smallbore re-entry match days earlier. Francis Parker of Illinois won the smallbore national title with 247 of 250, breaking a tie over Lt. A. M. Siler on the long-range stage. Grosvenor Wotkyns split the Dewar team into two coached relays and used all American equipment for the first time, posting 7779 to beat Britain by 23 points.

Marine Capt. William Ashurst won the National Individual Rifle Match with 291 of 300, including a 98 at 1,000 yards. Lt. Raymond Vermette topped the Board pistol title with 271. The Army Engineers, newly independent from the Cavalry, stunned the field by edging the Marines for the National Rifle Team Match. June 7, 1924 was declared National Rifle Day, with ranges across the country opened to the public and several cities sponsoring the travel of one junior to Ohio. Straight shooting had become a national expression.

1925 — New Leadership, New Identity and the Rise of Smallbore

Federal civilian funding continued, but the NRA and the National Board needed clearer public separation. Sharing an office in Washington’s Woodward Building had led many to assume that NRA membership meant War Department service. When the Board and the DCM moved out, the NRA’s civilian identity stood in sharper relief.

The year marked Lt. Col. Morton Mumma’s final season as Executive Officer. His tenure had guided Camp Perry through postwar uncertainty and the expansion of the program into more than 25 NRA events. The reins passed to Col. Alexander Macnab, Jr., at a moment when juniors and collegiate shooters were arriving in growing numbers. The Winchester Junior Rifle Corps camp entered its third summer, and by the following January the NRA would assume full control.

The printed program still called rifle the principal interest, yet it acknowledged the broadening appeal of pistol, especially among police departments. More importantly, it explicitly addressed the growing use of the phrase “National Matches” to encompass the entire experience, not just the four Board events. The event had become a unified enterprise.

Smallbore had matured into a destination of its own. Sgt. Thomas Imler of the Arizona National Guard won the national title with 248 across the three-stage any-sight course at 50, 100 and 200 yards. For the Dewar team, E. F. Shearer’s 398 led a squad of 20 shooters, 19 of them civilians. Their final score of 7791 beat the British by 38 points and extended the American holding of the trophy to nine straight years. Among the NRA long-range events, Capt. William Ashurst won the Wimbledon Cup, Lt. Pierson Conradt took the Leech Cup and Lt. Bruce Hill topped nearly 1,200 competitors in the President’s Match. The California civilian squad won the Herrick Trophy, and the Cavalry captured the Infantry Match. The decade’s midpoint felt like a handoff: new leadership, a clearer charter and smallbore ascendant.

1926 —NRA Holds the Line as Sea Girt Steps In

In 1926 the National Matches faced the kind of crisis that threatened to break the continuity the NRA had worked so hard to build. No federal funds were appropriated for the program. The cut was not tied to war or manpower demands. This time it was simple economy, a budget line struck out in Washington. NRA President Fred Waterbury and Executive Secretary Milton Reckord carried the case all the way to President Calvin Coolidge. Even Senate approval for minimal funding could not save the Matches once the House refused its support. As American Rifleman wrote that spring, the men “controlling the money-bags of the nation” had decided that one of the country’s strongest incentives to national defense was not worth a modest sum.

With Camp Perry no longer viable, the NRA pivoted. Sea Girt, New Jersey, emerged as the natural center of a regional plan. Brig. Gen. Bird Spencer, who had been instrumental in 1912 and 1914, again secured the grounds. The program ran from September 4 to 14 with Spencer as Commandant and Col. Douglas McDougal as Executive Officer. Five other regional competitions filled out the calendar at Fort Lawton, Fort Screven, Fort Sheridan, Wakefield and Harrisburg. None could replace Camp Perry, but together they kept the sport breathing.

At Sea Girt the Marines filled the void left by the Army’s absence, staffing pits and ranges and anchoring the firing line. Four sesquicentennial matches stood in for the National Board events, and Marine shooters claimed the major honors. Equipment shortages gave the Matches a makeshift quality. No issued pistols. No permanent Commercial Row. No family camp. The Dewar Match proved the most difficult, relocated to the high-power range with shooters moving repeatedly as ocean wind hammered the coast. Even the legendary coaching of men like Harry Pope could not overcome the swirling conditions, and for the first time in more than a decade the British reclaimed the Dewar Trophy.

Participation fell well below Camp Perry standards, and no competitor could realistically claim a national title. Yet the regional format carried the sport into places far from Ohio where shooters had their first look at NRA competition. As American Rifleman noted, the regional matches were “pleasant gatherings,” but they were not a substitute for the cherished format of the National Matches. Still, they kept the idea alive.

1927 — Benign Weather, Record Crowds and a Season of High Scores

Camp Perry returned to full strength in 1927. Federal support, restored through NRA advocacy and the backing of major national organizations, ensured that civilian teams could once again travel under government funding. For the first time the House Appropriations Committee explicitly recognized civilians in its allocation. Col. Alexander Macnab, Jr., resumed command.

The summer opened under weather so calm that American Rifleman remarked it “belied the camp’s reputation as a hell-bender weather breeder.” High scores followed, and attendance surged. A touch of history returned when Frank Kahrs of Remington located the long-missing Leech Cup, last seen in 1913. The junior smallbore camp, now fully under the NRA, grew steadily. Police presence increased with a new qualification course and classes in tear gas, submachine guns and quick-draw technique.

The National Individual Rifle Match reached a record 1,400 entries. Marine Lt. R. M. Cutts won the combined field by a single point over Texas civilian M. M. Works. The Infantry took the National Team Rifle Match after a Marine protest for a re-shoot was denied. Marines won the National Team Pistol Match, and Cavalry Sgt. B. H. Harris claimed the individual pistol championship. At long range Lt. Lewis Hohn won the Wimbledon Cup for the second consecutive year, and Pvt. First Class R. F. Seitzinger took the Leech Cup with 105.

Smallbore returned to a full national championship format with a new four-match aggregate designed to reward consistency with both metallic and any sights. Ralph McGarity of Washington, D.C., won the title, becoming the first two-time smallbore national champion. The U.S. reclaimed the Dewar Trophy with a record score, and a new postal contest, the International Railwaymen’s Smallbore Match sponsored by the Pennsylvania Railroad, debuted with a U.S. win over Great Britain.

1928 — Federal Recognition, New Ranges and the First Sound-Film Firing Line

NRA’s persistence finally carried all the way to Capitol Hill. On May 28, President Calvin Coolidge signed H.R. 13446 into law, guaranteeing annual funding for the National Matches and the Small Arms Firing School. It was the result of relentless negotiation by Brig. Gen. Milton Reckord and Congressman John Speaks of Ohio. Earlier, an amendment to the Army Appropriations Bill had already set aside $500,000 to ensure the 1928 National Matches would proceed. Congress had been persuaded that rifle practice was not a luxury but a national obligation.

Col. Hu B. Myers took over as Executive Officer and reinstated mandatory Small Arms Firing School attendance for all National Trophy team members without prior certificates. Camp Perry changed more in 1928 than it had in several prior seasons combined. A new pistol range with 70 targets rose on the former smallbore grounds. A new smallbore complex appeared at the west end of camp with bus service. High-power capacity expanded with 20 additional targets at 200 yards and 60 more at 1,000 yards.

For the first time in history the National Matches were filmed with synchronized sound. Fox Movietone arrived early in the program and captured moving images of the firing line with the crack of shots recorded as they were fired. American Rifleman called it a historic first: the firing line preserved not only in sight but in sound.

The Marines dominated the summer, sweeping all four Board events and controlling many NRA titles. The Herrick, President’s and Wimbledon Matches all fell to Marine riflemen, though the Leech Cup went to Navy Ensign C. H. Duerfeldt after he creedmoored Marine Sgts. J. F. Hankins and W. F. Pulver. Sgt. J. R. Tiete won the first Automatic Rifle Match, pouring unlimited rounds from a light Browning at 400 yards in 45 seconds.

The Coast Guard appeared at the Matches for the first time. Sixteen-year-old David S. McDougal, Jr., placed third in the President’s Match, then teamed with Lawrence Wilkens to win the Hercules Trophy in smallbore. Wilkens later fired a perfect 400 in the Caswell Cup, the first perfect Dewar Course score in history. Ohio’s V. Z. Canfield won the national smallbore title and led the Dewar team with 398. A record number of women competed that year. Tragedy punctuated the season when a pilot was killed during an air exhibition on Visitors Day before an estimated 15,000 spectators. Even so, 1928 stood as a milestone. With federal backing secured and the facility expanded, American shooters could look to the National Matches with confidence equal to their anticipation.

1929 — Record Crowds, Expanding Disciplines and a New Era of Civilian Strength

The National Matches of 1929 opened under clear skies and with a sense of confidence that had been missing for years. Thanks to the 1928 legislation guaranteeing federal support, shooters across the country knew the Matches were secure well in advance, and attendance reflected that certainty. More than 17,500 entries poured through the gates, an increase of nearly 4,000 over 1928. As American Rifleman noted, once through the gate “you begin to feel the pulse of the National Matches,” a rhythm that pulled shooters back year after year.

Col. Hu B. Myers again served as Executive Officer, guiding a program that ran from August 15 through September 15. The Marines did not hold the same sway as in 1928, though they still claimed the Herrick Trophy Match and the National Team Pistol Match. The Infantry won the National Team Rifle Match in a record field of 108 entries. The National Individual Rifle Match grew to 1,638 shooters, with Cavalry Sgt. J. B. Jensen taking the crown. In the President’s Match, Navy Ensign C. B. Coffin topped a field of 1,512.

Civilian and police competitors delivered some of the season’s most memorable performances. R. W. Ballard of Colorado became the first civilian since 1913 to win the Marine Corps Cup, besting more than 1,300 shooters. L. E. Wilson of Washington state earned the National Individual Pistol title, and the Massachusetts civilian team won the Infantry Match. Even the Chemical Warfare Match went to a civilian, R. G. Hansen of Utah.

Police involvement reached its highest level yet, with 18 teams competing. Two police squads finished first and second in the NRA team pistol match. Their dedicated range, instantly dubbed “Hogan’s Alley,” featured moving-vehicle Thompson submachine gun stages and disappearing target drills that anticipated modern police training. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police added international flair, finishing second to Portland, Oregon, in the first International Police Team Match.

International smallbore remained a highlight. The U.S. won both the Dewar and the Railwaymen’s Matches. Nineteen-year-old Mary Ward became only the second woman to qualify as a firing member of an American international rifle team and the only competitor to fire a possible at 50 yards. The national smallbore title went to famed barrel maker Eric Johnson of Connecticut after a tiebreak over 17-year-old Larry Wilkens.

What the 1920s Built

Across 10 years, the National Matches evolved from a postwar reset into a coherent culture. The Small Arms Firing School turned technique into a shared language. Smallbore moved from the margins to the middle, its Dewar battles binding American shooters to an international standard. Junior camps and police courses widened the circle. Federal recognition in 1928 guaranteed continuity. By 1929 the firing line at the National Matches mirrored the country that supported it: service and civilian, veterans and teenagers, a republic teaching itself to make one good shot, then another.