** When you buy products through the links on our site, we may earn a commission that supports NRA's mission to protect, preserve and defend the Second Amendment. **

Above: This pellet exited the muzzle in about 0.006 seconds, while it took the brain about .3 seconds to recognize the desired sight picture and move the trigger finger.

Muzzle Flip

Muzzle flip in an air rifle is an effect, not a cause. Because the barrel is above the center of mass (most of the stock, the trigger and the air cylinder), there is a bit of torque on the whole rifle, which is a variable addressed in high end, precision rifles. How much the barrel jumps depends on a lot of things. However, most of the jump is long after the pellet exits the muzzle. Moving up from .17 to .22 caliber is a lot more fun. All kinds of things happen during a .22 cal. shot, which is why tuners sometimes work, if set properly.

Follow Through

When you apply enough pressure to the trigger to make something happen (like firing the rifle), the pellet pops out the end in about 6 milliseconds (0.006 seconds). That’s not long— far less than the blink of the eye. And not much can happen in that time. However, from the time the brain decides it has a good sight picture until the finger can put enough pressure on the trigger to make this happen, is on the order of 0.3 seconds. A lot can happen in that time.

Like the brain moving on to something else. Ray Guffee Sr. called this “putting the ten away before you shoot it.” Thus, follow through begins before you actually shoot the shot. Once the trigger sear does its thing, you can’t really change much. In the old days of the RWS-75 and other slower air guns, this was not always the case. The Feinwerkbau 600 and successors were far faster, and the follow through we thought of after pulling the trigger went away. Staying mentally on the shot for the entire process did not change. That’s always been critical.

Like the brain moving on to something else. Ray Guffee Sr. called this “putting the ten away before you shoot it.” Thus, follow through begins before you actually shoot the shot. Once the trigger sear does its thing, you can’t really change much. In the old days of the RWS-75 and other slower air guns, this was not always the case. The Feinwerkbau 600 and successors were far faster, and the follow through we thought of after pulling the trigger went away. Staying mentally on the shot for the entire process did not change. That’s always been critical.

Looking at the physics, I suspect the puff of air does far more than the pellet to move things a bit. This can be measured in three ways: First, dry fire (some air guns can’t do it) and see what the firing pin by itself does to your sight picture. Second, shoot without a pellet. (I did this in a match once, resulting in a very well executed zero.) Third, measure sight movement with a fired pellet. You won’t find much difference, if any, with and without a pellet. I did all of this some years back with oscilloscope photos and measurements of barrel motion using electronic, non-contact micrometers with both air guns and .22s.

The “jump” or muzzle flip is partially recoil and partially the shooter’s position. A tight position may have less jump, although physiology (and trigger control) can affect this. The jump can be substantially reduced with an appropriate barrel weight—the Henrich Vibration Controller comes to mind. Even with a weight, however, the recoil along the barrel axis will not change much.

Olympic grade rifles incorporate some vibration dampening not found in sporters. High-velocity field rifles can be much worse, although I have little experience there.

Recoil

Recoil

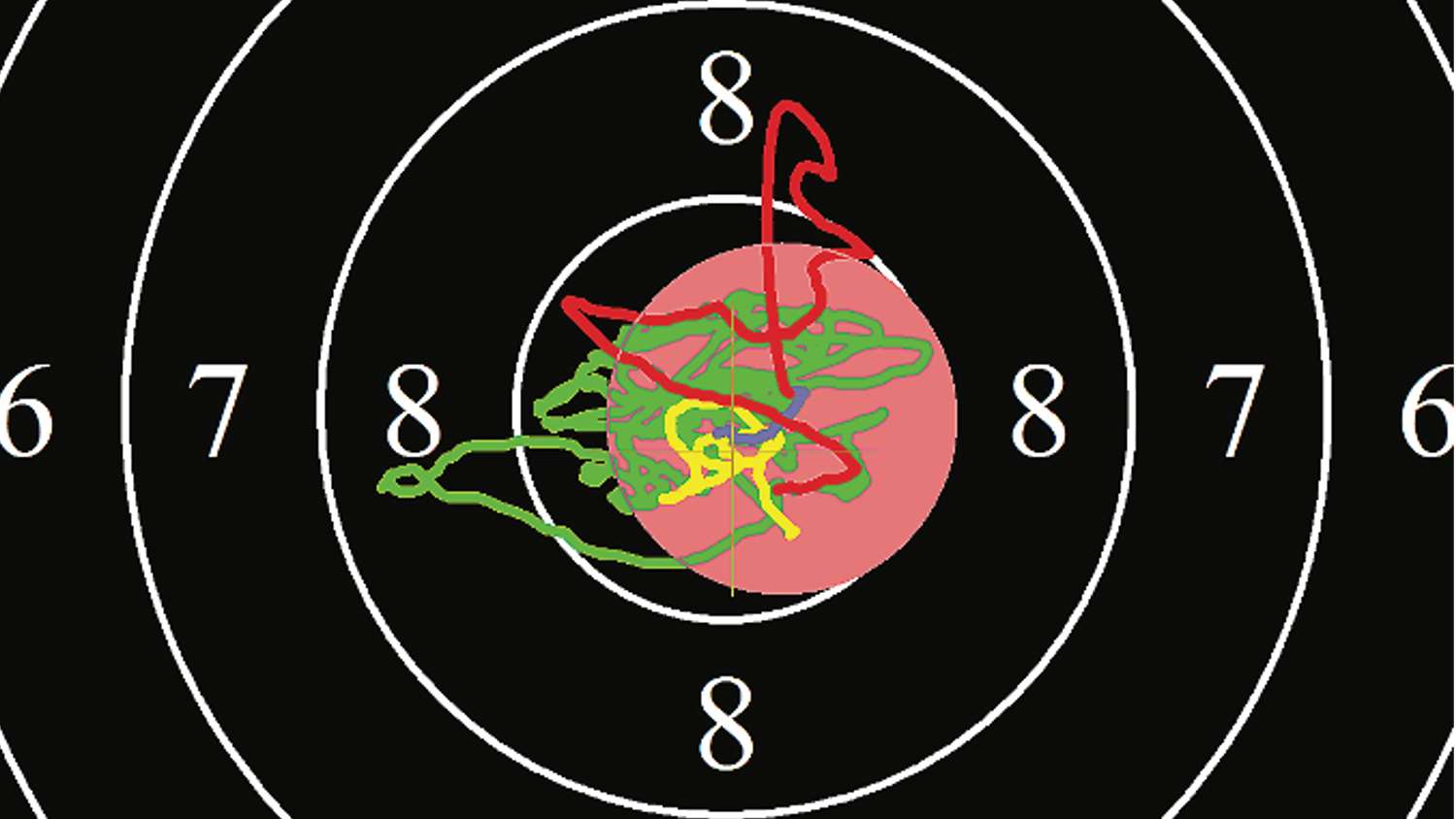

Linear recoil along the barrel is physics: Pellet and air out one end, gun recoils backwards in the opposite direction. Any barrel jump depends on this and several other factors. A SCATT trace will show some jump, perhaps a bit less that we see with the laser at the Olympic Shooting Center. This could be due to frequency limitations of SCATT or differences in rifle / shooter position. Our observed jump is usually shorter than SCATT in duration, but perhaps a bit larger in amplitude, as measured with many shooters firing many shots, over many years (and with many different rifles).

About the Author:

Tim Conrad was a competitor and assistant coach in the 1990s as well as a member of the Shooting Sports Research Council for USA Shooting. He was the chief engineer for a machine tool company in Chicago, and has been in the measurement and control business for more than 40 years. Says Tim: “I haven’t made all the possible mistakes, but the day isn’t over.”

Muzzle Flip

Muzzle flip in an air rifle is an effect, not a cause. Because the barrel is above the center of mass (most of the stock, the trigger and the air cylinder), there is a bit of torque on the whole rifle, which is a variable addressed in high end, precision rifles. How much the barrel jumps depends on a lot of things. However, most of the jump is long after the pellet exits the muzzle. Moving up from .17 to .22 caliber is a lot more fun. All kinds of things happen during a .22 cal. shot, which is why tuners sometimes work, if set properly.

Follow Through

When you apply enough pressure to the trigger to make something happen (like firing the rifle), the pellet pops out the end in about 6 milliseconds (0.006 seconds). That’s not long— far less than the blink of the eye. And not much can happen in that time. However, from the time the brain decides it has a good sight picture until the finger can put enough pressure on the trigger to make this happen, is on the order of 0.3 seconds. A lot can happen in that time.

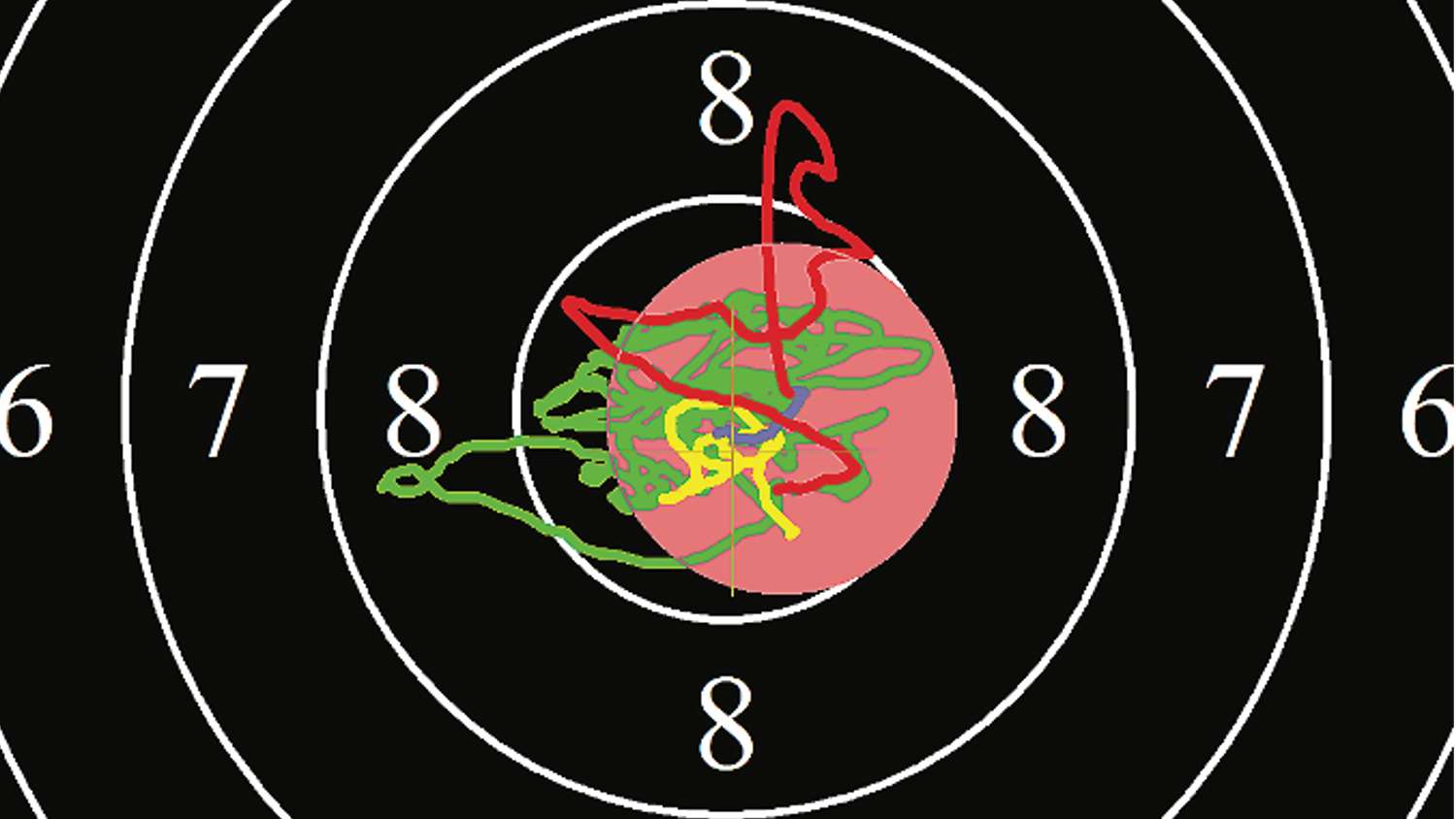

This sample SCATT target depicts the shooter’s shot sequence where GREEN represents the shooter’s hold; YELLOW—muzzle movement during the last second before the shot; BLUE—.2 seconds before the shot and RED—recoil for one second after the shot.

Looking at the physics, I suspect the puff of air does far more than the pellet to move things a bit. This can be measured in three ways: First, dry fire (some air guns can’t do it) and see what the firing pin by itself does to your sight picture. Second, shoot without a pellet. (I did this in a match once, resulting in a very well executed zero.) Third, measure sight movement with a fired pellet. You won’t find much difference, if any, with and without a pellet. I did all of this some years back with oscilloscope photos and measurements of barrel motion using electronic, non-contact micrometers with both air guns and .22s.

The “jump” or muzzle flip is partially recoil and partially the shooter’s position. A tight position may have less jump, although physiology (and trigger control) can affect this. The jump can be substantially reduced with an appropriate barrel weight—the Henrich Vibration Controller comes to mind. Even with a weight, however, the recoil along the barrel axis will not change much.

Olympic grade rifles incorporate some vibration dampening not found in sporters. High-velocity field rifles can be much worse, although I have little experience there.

A stable position is critical for consistent recoil management.

Linear recoil along the barrel is physics: Pellet and air out one end, gun recoils backwards in the opposite direction. Any barrel jump depends on this and several other factors. A SCATT trace will show some jump, perhaps a bit less that we see with the laser at the Olympic Shooting Center. This could be due to frequency limitations of SCATT or differences in rifle / shooter position. Our observed jump is usually shorter than SCATT in duration, but perhaps a bit larger in amplitude, as measured with many shooters firing many shots, over many years (and with many different rifles).

About the Author:

Tim Conrad was a competitor and assistant coach in the 1990s as well as a member of the Shooting Sports Research Council for USA Shooting. He was the chief engineer for a machine tool company in Chicago, and has been in the measurement and control business for more than 40 years. Says Tim: “I haven’t made all the possible mistakes, but the day isn’t over.”