My version of “Murphy’s Law” is that if things will go wrong, they’ll go wrong on match day. But with contingency planning, even the worst catastrophe can be handled as just another incident in a day’s shooting.

Contingency planning means having a response ready for everything that might happen to you in a match. Before you travel to a match, particularly if you’re going abroad, you should have a plan ready for coping with every possible thing that might happen. In addition to preventing surprises and helping you deal with problems, contingency planning gives you tremendous confidence, since it prepares you for anything. It is one way to make up for the fact that other shooters may have more experience than you.

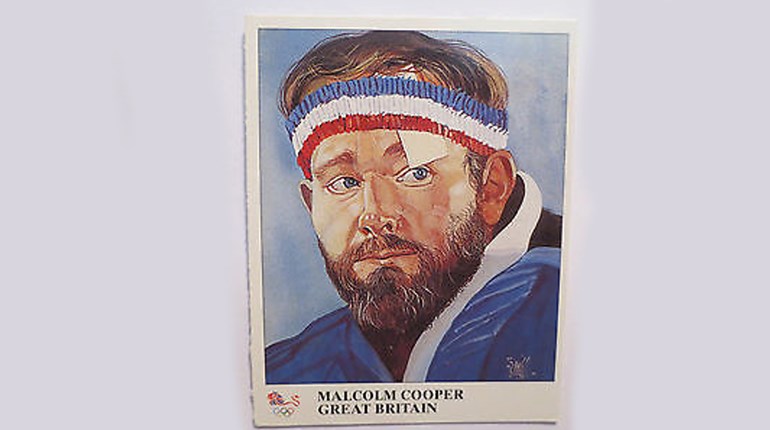

Two days before the 1988 Olympic three-position match, a TV cameraman kicked my rifle over and broke the stock almost all the way through the grip. Instead of panicking, my reaction was to calmly find a way to get the stock fixed. I had planned what to do if my stock was broken. I always carry a repair kit with tools and epoxy for just such a problem. I did go see the Russian armorer, who had a work area. He had better glue than I did so we used it and worked on the gun together.

I lost one training day fixing the stock. When I tested the gun the next day, my groups seemed to be vertical, and I was afraid something was wrong with the glue job. (Because the barreled action was glued rather than bedded, I had had to repair the stock with the action in it.) I left it alone, and at the end of the last training session before the match, I tested a different lot of ammo. The groups seemed more round, and I used that ammo for the Olympics. The lesson, of course, is that by being prepared for the worst I solved the problem and it didn’t affect my ability to win.

Some confuse contingency planning with negative thinking, but such preparations can easily be made without focusing on the negative. While you are thinking of what could go wrong, your focus is on preparing your response. What would be negative and detrimental to your performance would be to plan what you will say to your friends, or to worry about what they will say when you don’t do well.

List the items that Murphy’s Law says will happen sooner or later in a match. You might include, for example: poor light, hot or cold weather, heavy mirage, broken target mechanisms, difficult range officials, gun breakdown, jet lag, being late, unusual food, problems with equipment control, etc. Then develop a plan to deal with each one. If I can’t work out in my mind how I might deal with a problem, such as an uneven firing point, I go to the range and practice with that problem until I work out a solution.

Perhaps even more important than planning for what might go wrong is to plan for what might go right! You should be prepared to have a really good day, which everyone does. Think what it will feel like to get through the last position, or the final, and finish with a really good day. Imagine what it will feel like to shoot a record score. Imagine what will happen when you win, even what it will feel like to stand on the awards rostrum and receive your medal.

Many shooters fail to prepare themselves for doing really well. Consequently, when they start to do better than normal, they can panic, shoot a few bad shots and end up with a score close to their average, one they are comfortable with. If a shooter has thought about winning and what it will mean, when the time comes, winning will be much easier. Thinking about such cases during quiet times off the range is a good investment for the future on the range. All of this is “thinking” training and therefore all part of mental training.

While I don’t actually rehearse shooting a perfect score, I work very hard to convince myself that the top end of my scoring is open. I know that the harder I train the better technique I will develop, and the envelope, or range of scores I can shoot will become smaller. Both my best scores and my worst scores will rise. I don’t limit myself by saying this is the most I can achieve. The top end is always open.

To summarize, spend time planning how you will deal with anything that might happen in a match. Think about each thing that could go wrong and work out a plan to deal with it. Think about how things could go right and what it will feel like when they do. Know what you will do. Having a plan for every situation will prevent surprises, make you better able to deal with whatever happens and boost your confidence.