The year 1935 was magical for handgunners. To begin with, it was the first time a mainstream manufacturer had produced a handgun and ammunition designed for daily operation in the 40,000-psi range. Second, it introduced the word "magnum" to the handgun shooting public. Third, it initiated the concept of handgun hunting as a legitimate sport. As you have probably guessed, 1935 was the year that Smith & Wesson and Winchester introduced the .357 Magnum.

The 40,000 psi pressure level may seem like no big thing today, but in the 1930s, it was a giant step from the low pressures previously allowed in handguns and handgun ammunition. It paved the way for everything that followed in the development and evolution of high performance handgun cartridges.

No matter that bold experimenters and wildcatters told their stories of custom guns and handloaded ammunition. Until something is endorsed and built by a legitimate production company and made available in the marketplace, it is not a reality to the general public. And while the word "magnum" has been repeatedly cussed and discussed in the past, it brought an element of breathless excitement to the shooting community never imagined by the champagne sippers. Finally, for handgun hunters, the .357 Magnum's introduction induced dreams from beyond our imagination and allowed those dreams to flow into an incredible reality of hardware and personal experiences.

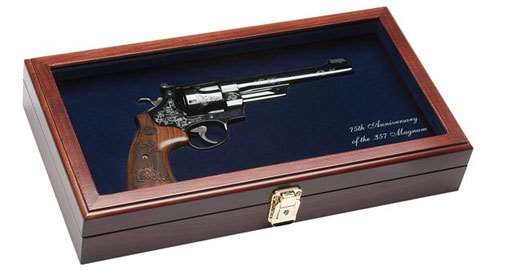

The first Smith & Wesson magnum was an elegant offering with a barrel length of 8 3/4 inches. No need for a model number assignment, it was simply called the ".357 Magnum." The first guns were given special registration numbers and shipped with certificates describing the specific features of each gun. These initial guns produced a reported muzzle velocity of 1,550 FPS.

Doug Wesson wasted no time in heading west to try the new combination, quite successfully, on a variety of big game animals ranging from antelope through elk, grizzly bear and moose. While no one today would advocate taking game larger than deer with a .357 Magnum, Mr. Wesson's achievements did cause a paradigm shift on handgun hunting big game. That shift led to the subsequent invention and production of much more powerful handguns and cartridges that are suitable for hunting anything that walks this planet.

The initial .357 Magnum became the Model 27, and prior to its recent deletion from the Smith & Wesson production line, it was offered in barrel lengths of 3 1/2, five, six, 6 1/2, and 8 3/8 inches. The same sized frame (called the N frame) was used for Smith & Wesson's subsequent magnums, the .41 and .44. The only problem with the Model 27 was the barrel protruded into the window of the frame that houses the cylinder. This dictated a shorter cylinder that in turn limited the overall length of the loaded cartridge which forced the heavier, more desirable bullets deeper into the cartridge case reducing powder capacity. Despite this limitation, the Model 27 was an outstanding handgun, particularly when used with bullets up to 160 grains in weight.

Perhaps the greatest testimony to the .357 Magnum's flexibility as a cartridge is the tremendous selection of revolvers still chambered for it today. These range from the two-inch barreled revolvers made of titanium, scandium, aluminum and steel weighing slight more than 10 ozs., to the majestic Desert Eagle weighing more than four lbs.

Clearly the little two-inchers were never intended for hunting grizzlies, and the Desert Eagle wasn't designed as a pocket-carry gun, but a two-inch alloy revolver can save you from a predator much more frightening than a grizzly, and no .357 Magnum is gentler to shoot than the big Eagle.

A step up in size from the skeletal lightweight double-action revolvers with their notched-frame rear sights are similar, small framed revolvers carrying the additional weight that comes with steel. These sport barrels from two to four inches, and some are equipped with more visible, adjustable rear sights.

Jumping one more frame size buys you more mass to absorb recoil, a higher capacity of stored ammunition and barrel lengths from 2 3/4 to eight-plus inches. With adjustable sights on a medium frame and a barrel around 3 1/2 to four inches, you can start handgun hunting smaller varieties of big game. A barrel longer than four inches on a medium or large frame .357 Magnum with good adjustable sights allows you to enter fairly serious handgun hunting country. The double-action revolver field is well-covered today with quality offerings from Smith & Wesson, Taurus and Ruger.

Single-action revolver fanciers have not been ignored in today's market. Ruger built its first .357 Magnum in the mid-1950s when the flood of TV westerns created a demand for "cowboy" guns that could not be met by Colt. With typical Ruger brilliance, the .357 Blackhawk was designed to be inexpensively produced and virtually indestructible. The gun has evolved some in terms of frame size, internal safety systems and design of the adjustable rear sights, but the original si-gun is instantly recognizable in today's models.

An influx of cheap, military ammunition prompted Ruger to begin manufacturing its Blackhawk convertibles, and the .357 Magnum with an extra cylinder chambered in 9mm began showing up on dealers' shelves in 1967. A change in caliber/cylinder takes about five to 10 seconds, requires no tools, and results in no modifications to the gun. you will probably have to adjust the rear sight when switching cylinders, just as you would if changing .357 Magnum loads. The 6 1/2-inch barrel Ruger .357 Magnum might be a better handgun hunting choice than the 4 3/4-inch barrel, but you could hunt a lifetime with either one and proudly pass it on to the next generation.

There are a multitude of 1873 Colt Peacemaker replicas built from parts made in Italy and offered by Cimarron, EMF and Navy Arms in .357 Magnum. These are fun to shoot, come in several different barrel lengths and recreate the nostalgia of the Old West. While the guns I've used are well-made, the non-adjustable sights duplicate those on the original Colts with a small, "V" notch in the frame and a skinny blade up front. Ruger's Vaquero model is slightly larger in frame size has a much more visible square notch in the frame and wider blade up front. It will handle heavy .357 Magnum loads with less wear on either the gun or the shooter.

For the utmost in quality and accuracy, along with an attendant increase in price, you can select a single-action .357 Magnum by Freedom Arms. Its Model 83 is the same frame that handles the .454 Casull, which generates pressures in excess of 50,000 psi. FA's smaller frame Model 97 is slightly smaller than the Ruger frame, but easily handles full factory load .357 Magnums that stay under 40,000 psi.

The Desert Eagle is a large, gas-operated handgun that is incredibly gentle to shoot with the heaviest .357 loads. Between the gun's weight and the gas-cycled rotary bolt, this is the gun that will let anyone with adequately sized hands shoot his/her first magnum. Because of the gas channel under the barrel potentially getting clogged with lead from cast bullet loads, the manufacturer recommends that you shoot only jacketed bullets. But for a fun afternoon of gentle therapy, take an Eagle on a date with all the jacketed or plated bullets you can carry.

We cannot neglect single-shot pistols. Rate of fire is certainly slower than either a revolver or semi-automatic, but the longer barrels and absence of any gas venting between barrel and cylinder will give you increased velocity for any given load. There are no barrel-cylinder alignment concerns as there are in a revolver and no requirement that the ammunition be tailored to cycle the action as in a semi-automatic. The single-shots I've fired in .357 Magnum have all been extremely accurate, whether made by Thompson/Center, Rock Pistol Manufacturing, Springfield Armory or MOA. In addition, the single-shots virtually beg to have some kind of optical sight mounted so that you can fully realize their accuracy and range potential.

The variety of handguns chambered in .357 Magnum is no more astounding than the multiplicity of ammunition available for them. Jacketed hollow points weighing 110 to 125 grains provide plenty of defensive pop in the small frame revolvers while keeping recoil well below that of the heavyweight bullets. Jacketed hollow points and soft points from 125 to 160 grains work well on game up through small deer. Jacketed bullets up to 18 grains will handle the deer family up through reasonably sized mulies.

With a 180-grain bullet like the Winchester/Nosler Partition Gold, or the Hornady XTP, fired in a gun that produced velocities of 1,100 FPS, I would be comfortable hunting mule deer. I'm not sayhing the . 357 Magnum would be my first choice of calibers, and I would not take a "Texas heart shot" unless the animal was already wounded, but I wouldn't hesitate to go on the hunt.