At the Winter Olympic Games, biathlon unfolds as a study in contrasts. Athletes glide across snowbound trails at full exertion, then arrive suddenly at stillness, tasked with calming breath and muscle to strike distant targets. It’s a race measured not only in seconds and meters, but in heartbeats and decisions. At the Milan Cortina 2026 Winter Olympics, this balance between motion and restraint will again define one of the Games’ most demanding competitions.

Biathlon combines rifle target shooting and cross-country skiing, with each event beginning and ending on the ski course. Depending on the format, athletes complete multiple loops punctuated by shooting bouts in prone and standing positions. Missed targets carry consequences. Some events impose a one-minute time penalty, others require a grinding 150-meter penalty lap that must be skied before rejoining the race. Victory belongs to the athlete or team that completes the course with the lowest calculated time or, in head-to-head formats, reaches the finish first.

The sport’s roots stretch back long before Olympic podiums. Biathlon evolved from hunting traditions and military patrols in snowbound regions, where survival demanded both endurance and accuracy. It appeared at the first Winter Olympic Games in 1924, though disagreements over rules delayed its official recognition. The modern era began with the first World Championships in Austria in 1958, followed by Olympic inclusion at Squaw Valley in 1960. Women’s biathlon would not join the Olympic program until 1992, a late but transformative addition that expanded the sport’s competitive depth.

Today’s biathlon is raced with smallbore rifles on ski courses ranging from explosive sprints to endurance-heavy individual races. Distances vary by event and gender, from 10 km for men’s sprints and 7.5 km for women, up to the 20 km men’s individual and 15 km women’s equivalent. There is also a mixed 4x6 km relay race. Each race includes two or four shooting bouts at the range, evenly divided between prone and standing. Precision matters as much as speed. Every missed shot reshapes the race, either by adding time or forcing an athlete into the penalty loop.

The equipment itself reflects decades of refinement. Early biathlon competitions used high-power, centerfire rifles and shooting distances of up to 250 meters. By 1978, the sport standardized on the smallbore format and today’s 50-meter range. Mechanical, self-indicating targets—introduced at the 1980 Lake Placid Games—flip from black to white when struck, providing instant confirmation to athletes and spectators alike. That immediate feedback is often accompanied by a roar from the crowd. At the Milan Cortina 2026 Winter Olympics, biathlon competitions will use automated target systems that sense hits and misses quickly, allowing for rapid scoring and spectator visibility. Paper targets remain for practice and zeroing duties.

During competition, athletes arrive at the range with heart rates approaching 180 beats per minute. From that state of exertion, they must fire five accurate shots in rapid succession. In relay events, the pressure intensifies further. Each athlete has eight bullets to clear five targets, with the final three rounds loaded manually, one at a time. Miss after eight shots, and the penalty loop awaits—one lap for every target left standing. The margin for error is slim, and the cost of hesitation is high.

Among the most dramatic formats are the pursuit and mass start. In a pursuit, athletes begin the race staggered by results from a previous event, typically a sprint, turning the course into a moving countdown. The first skier to catch and pass rivals on the final lap wins. Mass starts, by contrast, release the entire field at once, creating a tightly packed opening lap before the race gradually fractures under the combined weight of speed and missed shots. Safety and fairness dictate lane assignments early, before the chaos gives way to order.

Relays bring a different rhythm, echoing track-and-field exchanges but on snow, rifles still slung across backs. Each touch between teammates carries not only momentum, but responsibility. A single missed target can undo minutes of hard skiing done by those who came before.

All skiing techniques are permitted, but athletes may use nothing beyond skis and poles to propel themselves. The rifle, weighing at least 3.5 kilograms without ammunition, is carried throughout the race—a constant companion and a reminder that no part of biathlon is easy.

At Milan Cortina 2026, biathlon will once again present its full slate of 11 Olympic events, each offering a different lens on the same essential challenge:

- Mixed 4x6 km Relay

- Men’s 20 km Individual

- Women’s 15 km Individual

- Men’s 10 km Sprint

- Women’s 7.5 km Sprint

- Men’s 12.5 km Pursuit

- Women’s 10 km Pursuit

- Men’s 4x7.5 km Relay

- Women’s 4x6 km Relay

- Men’s 15 km Mass Start

- Women’s 12.5 km Mass Start

Together, these races form a portrait of a sport unlike any other in the Olympic program. Biathlon does not reward speed alone, nor precision in isolation. It belongs to those who can master both at once, under the scrutiny of the crowd and the unforgiving arithmetic of penalties. In the mountains of Italy, Milan Cortina 2026 will ask the same timeless question: who can move fastest, stop cold and still hit the mark?

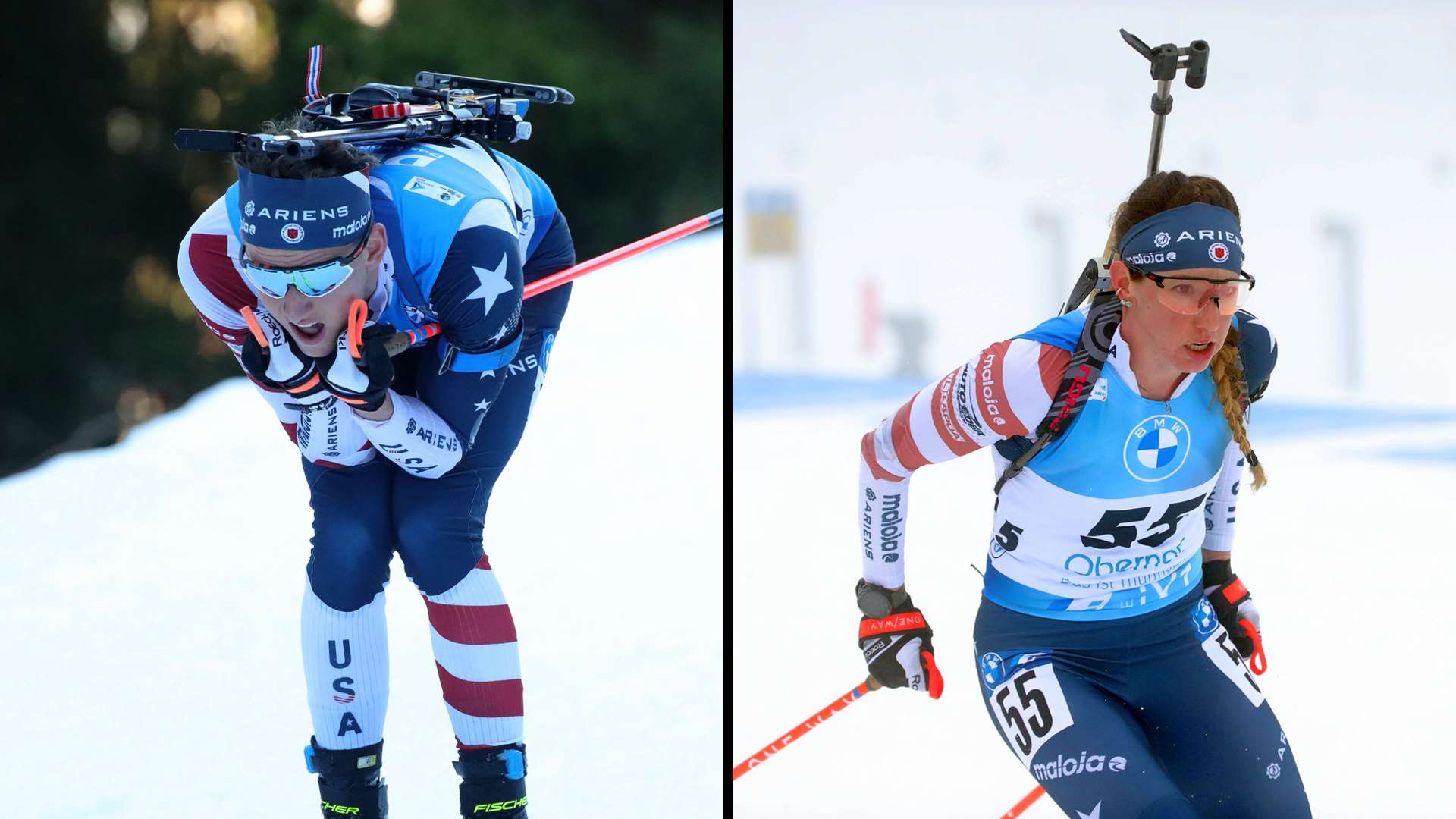

Team USA at Milan Cortina 2026

Team USA heads to Milan Cortina 2026 with a talented biathlon squad.

Deedra Irwin returns after her historic seventh-place finish in the women’s 15 km individual race at the Beijing 2022 Olympics, the best individual result ever for an American.

Campbell Wright is the top American men’s biathlete and secured silver in the sprint and pursuit at the 2025 World Championships. He previously competed for New Zealand at the Beijing 2022 Games.

Maxime Germain is making his Olympic debut, securing his spot on Team USA after posting three top 30 World Championship results in 2025.

Lucinda Anderson is also making her first Olympic appearance, having competed for the University of New Hampshire skiing team.

Joanne Reid heads to her third Olympics and is a former NCAA cross-country champion from a family of Winter Olympians.

Paul Schommer returns for his second Games after placing seventh in the mixed relay in Beijing.

Sean Doherty, the veteran of the team, is making his fourth Olympics and was Team USA’s youngest biathlete at just 18 in 2014.

Margie Freed completes the squad in her Olympic debut. She competed for the University of Vermont ski team.

Among a talented U.S. Biathlon team in Italy this week, Irwin remains a bright hope for a U.S. individual podium finish.