Top shooters I’ve spoken with have earned their classification the old fashioned way—through hard work. While one champion I interviewed seems to have been born with the right “programming” for competitive shooting, most became masters through years of climbing, rather than standing in line for the helicopter ride to the mountain top. We’ve all been tempted to purchase, make or borrow a new gizmo to help leapfrog us into the winner’s circle. After all, confidence in our equipment is a good thing. My weakness is late at night, staring at a website that offers a trigger, sight or ammunition that will expedite my ascent on Mt. Everest, a place I very much want to visit. So here’s an infomercial—not for an accuracy pill, but for an attitude that will help us to shoot better.

In a discussion with someone who has “walked the walk” in competitive shooting sports, I was reminded of something I teach, but haven’t used in my own plans for better shooting. What I had known, but paid too little attention to recently, was this: To override a million years of what evolution has taught us about loud noises that are 20 inches from our face, we need to repeat (practice) the desired actions of a consistent hold and trigger squeeze until *that* message is louder than what is being shouted by our evolutionary “lizard brain.” Like bulldozing a new riverbed for a centuries-old river, it takes time. No websites. No gizmos.

I thought I could return to competitive shooting after decades like riding a bike. The knowledge was there, ready to be dusted off. But my “shooting circuits” that were bulldozed back in the 1970s had been reclaimed by the centuries-old river of fight or flight; to flinch from a loud noise. Through a stubborn mind-over-matter approach, I was able to muscle my lizard brain into submission, but only occasionally. With the slightest distraction, my instinctive brain would wiggle out from my strong hold and win the wrestling match—meaning I shot poorly.

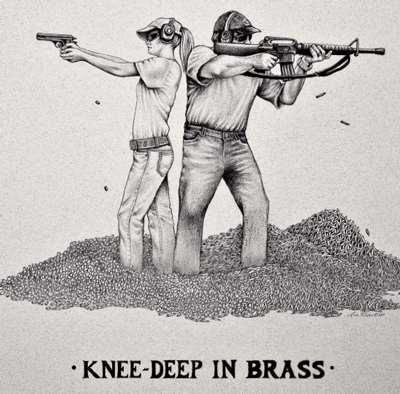

So, with tail somewhat between my legs, I have resigned to becoming “knee deep in brass” until my rehearsed logic circuit is stronger than my lizard brain’s concern over muzzle blast. Now, where is a good place to set up my reloading bench?